30 years later: Is Temik still a threat to East End?

Temik, the once-feared pesticide that contaminated thousands of East End wells more than 30 years ago, is not only all but forgotten, it’s all but gone.

And that’s just what scientists hoped and predicted.

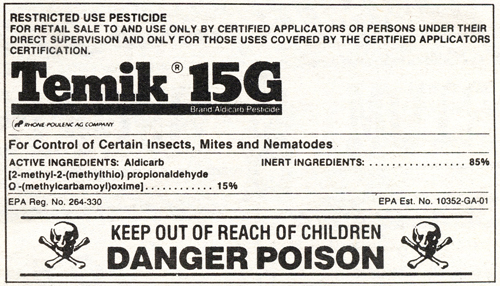

After the chemical aldicarb, sold under the brand name Temik, appeared in drinking water samples in the late 1970s, the manufacturer was pressed into providing activated charcoal filters for thousands of East End wells, including some feeding into public water systems. Knowing that there was no way to mechanically remove it all, county health department and other researchers suggested that the compound would continue to break down in groundwater and follow its slow flow toward the shore.

Results of the most recent health department well water tests found five of 317 private wells, or 1.6 percent, and one out of 929 public wells, or 0.1 percent, showing traces of Temik above the state guideline of seven parts per billion.

“Temik is a very interesting case study,” said North Fork Environmental Council president Bill Toedter. “There was a 30-year lag time between widespread use and the later discovery of the degree of danger of the substance and its eventual ban.”

The impacts have lessened, but Mr. Toedter and Group for the East End president Bob DeLuca believe the threat remains.

“The thing to keep in mind in all of this is whatever we put in the ground 20 or 30 years ago is still leaching down in the centuries-old aquifer,” said Mr. Toedter. He said the once-pristine Magothy aquifer, a water source found below the topmost upper glacial aquifer, the source of most North Fork private wells, now contains traces of nitrogen and other contaminants.

“Aldicarb and its metabolites are also finding its way into surface waters and are now discharging into the Peconic Estuary,” said Mr. DeLuca. “It’s one of the factors being looked at by the estuary as an item of concern.”

Mr. Toedter believes that’s what brought Long Island Farm Bureau executive director Joe Gergela and Long Island Pine Barrens Society executive director Dick Amper, who are often foes, together during state Senator Ken LaValle’s environmental roundtable last month. Both said more study is needed on pesticides and their effect on groundwater.

“That was the first time I’ve heard them publicly agree we need to study pesticide and fertilizer,” Mr. Toedter said.

Mr. Gergela said the farm bureau is currently working cooperatively with the DEC on its Long Island pesticide use management plan for several pesticides found in the groundwater.

The plan’s goal is to prevent “adverse effects to human health and the environment” without putting farmers and other pesticide users out of business, according to the DEC website.

Mr. Gergela said the key is finding a happy medium in agricultural pesticide use, given that a zero tolerance policy is unrealistic.

“Whatever we do on land goes into the groundwater; that includes gasoline,” he said. “What are we going to do, ban cars and trucks?”

If New York City couldn’t use pesticides to exterminate rats or roaches, he added, “we’d have public health epidemics.”

Mr. Toedter agreed that a zero tolerance policy is not currently viable, but even so, he said, the importance of keeping contaminants out of the water supply has never been greater.

“We need to make sure the lessons of Temik aren’t repeated,” he said. “We’re very lucky on the East End to have an abundant supply of clean water, but we’re in danger of losing it. It’s in our interest to protect our water. Without it, we’re all up a creek.”

Aldicarb was highly effective in controlling the Colorado potato beetle, a voracious insect that can strip potato fields of above-ground vegetation. The chemical was added to the soil when seed potatoes were planted. As a systemic, it was carried throughout the plant, poisoning insects as they fed on the leaves.

But product safety tests did not take into account Long Island’s sandy soils, which allowed the compound to reach groundwater long before it could break down.

Temik’s by-products, aldicarb sulfoxide and aldicarb sulfone, were first found in the North Fork’s well water in 1979 and the product was pulled from the Suffolk County market the following year at the request of its original manufacturer, Union Carbide Corporation.

At that time, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said extensive testing would have to be done on the East End to determine how long what it called the “most toxic chemical ever registered” would remain an item of concern in the water supply. No tests were done prior to its use in Suffolk County to see whether Temik could leach through the soil into the aquifer.

Temik was used on more than 2,000 acres for four growing seasons before Union Carbide requested that the EPA ban it in June 1980. The EPA called the voluntary ban “unprecedented,” according to Dennis Holt, a spokesperson for the company.

During June 1980 samples from 7,183 wells were tested for Temik. The results showed 13 percent with levels above seven parts per billion and 26 percent with a detectable level.

One month later, nearly 8,000 East End wells had been tested. Then-county executive Peter Cohalan announced that Union Carbide had agreed to install “sophisticated activated carbon” filters at no cost to homeowners for wells testing at seven ppb or higher. The company also installed large activated carbon filtration units for Greenport’s contaminated public water supply.

By November 1982, the county Department of Health Services said 1,500 Temik filters had been installed at $650 per filter.

Testing continued throughout the decade, particularly when pesticide levels began to rise in Greenport during the spring of 1983, which many believed was due to record rainfall.

A class action suit brought against Union Carbide was conditionally settled in the beginning of 1985 and included the payment of no less than $25,000 to a Temik research project at Cornell University’s Center for Environmental Research.

By 1989, there were 3,241 Temik filters on Long Island and 9.3 percent of wells tested showed Temik contamination.

The product is currently owned by Bayer CropScience, which in 2010 announced it would phase out Temik worldwide by 2014.

The EPA refused to reregister the chemical, saying it failed to meet new dietary risk assessment standards.

The county health department will not finish analyzing samples collected last year until the end of March, according to department spokeswoman Grace Kelly-McGovern. In 2010, however, 16 of 703 public community water supply wells sampled showed detectable levels of aldicarb, but none exceeded seven ppb.

Of 514 private water supply wells sampled in 2010, 20 had detectable levels of aldicarb and four of those had levels exceeding national guidelines. Ms. Kelly-McGovern said the majority of wells testing positive for aldicarb in 2010 were on the North Fork, although it was also detected at the time in Huntington on the South Fork.

The free filter program remains in effect for wells above the federal limit as long as necessary.

“If the resident opts for filtration, the Bayer CropScience program pays the expense of installation and maintenance, Ms. Kelly-McGovern said. “Bayer also provides filters for public supply wells that exceed the drinking water standard, as needed.”

Homeowners can request their drinking water be sampled and analyzed though the health department’s well sampling program.