Remembering the ‘L.I. Express’ hurricane of 1938

Sept. 21, 1938, was shaping up to be just another gray day on the North Fork for 5-year-old Verna Campbell.

Her Wednesday morning at the newly built Pulaski Street School went along like any other day, from what she can remember.

In Riverhead and across the Northeast, no one appeared to be fazed by reports of a hurricane speeding up the East Coast. School children like Ms. Campbell and then-high school junior Lewis Tomaszewski were sent to school as usual, because experts believed the storm had missed the southern states and was headed out to sea.

That morning’s New York Times editorial only boosted people’s confidence. The editorial hailed the U.S. Weather Bureau’s “unparalleled warning system” for alerting the public to inclement weather. The Times’ opinion piece focused on the hurricane that was expected to slam Florida, but turned eastward, avoiding landfall.

That same day, the bureau’s advisory out of Washington, D.C., made no reference to the hurricane, which even the most seasoned meteorologists assumed was destined to fizzle out in the Atlantic.

But by mid-afternoon, the wind had begun to pick up.

Hurricane outlook: When will the next big storm hit?

Mr. Tomaszewski remembers waiting for school buses to arrive to take the students home, watching through the windows as the hurricane struck.

“You could see these trees falling,” Mr. Tomaszewski — now 92 years old — told the News-Review.

In her kindergarten class, Verna Campbell and her classmates watched as the storm whipped through the nearby cemetery.

Video: Relive the Hurricane of ’38

“I was so frightened,” Ms. Campbell recalled. “The sky was gray and eerie and very terrifying. I wanted so desperately to go home.”

Not long after that, the hurricane that would become known as the “Long Island Express” unleashed its fury on the East End.

•

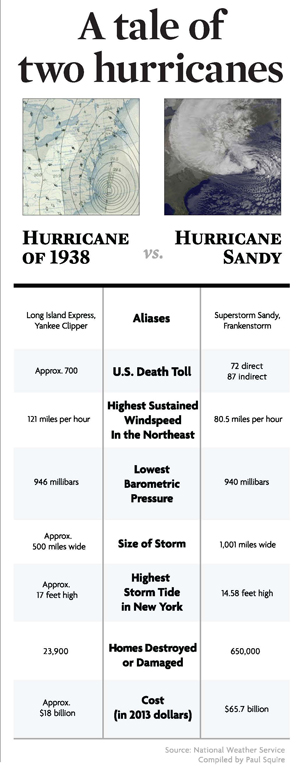

Seventy-five years later, that hurricane — known officially as the New England Hurricane of 1938 — has gone down in the record books as one of the most powerful and costliest storms ever to hit the region.

It slammed into the Northeast as a Category 3 hurricane with wind speeds gusting to more than 120 mph, toppling nearly two billion trees, according to National Weather Service estimates. A wall of water estimated at 17 feet crashed over Long Island. The storm made landfall on the South Shore sometime between 2:10 and 2:45 p.m. As quickly as the storm struck, it was gone, barreling across Long Island Sound into Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts within hours.

It slammed into the Northeast as a Category 3 hurricane with wind speeds gusting to more than 120 mph, toppling nearly two billion trees, according to National Weather Service estimates. A wall of water estimated at 17 feet crashed over Long Island. The storm made landfall on the South Shore sometime between 2:10 and 2:45 p.m. As quickly as the storm struck, it was gone, barreling across Long Island Sound into Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts within hours.

As many as 700 people were killed.

Related: How to prepare for the next big storm

“Homes were washed away, roads were washed away, Long Island Rail Road tracks were washed out, any of the fishing industry out here out east is gone, the apple crop was destroyed, a lot of livestock and farming was destroyed,” National Weather Service meteorologist David Stark said in a recent interview. “This was a very powerful, very destructive storm no matter how you look at it.”

Speed was partly to blame for the devastation, Mr. Stark said.

The hurricane traveled as fast as 60 mph up the coast — faster than any other storm in recorded history — after it got caught in the jet stream.

Without modern-day technology like satellites and radar, Long Island was caught off guard.

“Back then we were relying on data from ships going across the Atlantic,” Mr. Stark said. “They were thinking it was a tropical storm at that point. They didn’t really see [its] actual strength.”

Related: Pieceful Quilting, 11 months after Sandy, rebounds

Westhampton Beach bore the brunt of the hurricane’s force. The village area was flooded under eight feet of water. A movie theater filled with customers enjoying a matinee reportedly was lifted off its foundation by the storm’s waves and carried two miles out to sea, where it sank – drowning all inside.

While the damage in Riverhead was nowhere near as severe as in Westhampton Beach, the town suffered the “most savage storm in years,” according to an article in the County Review. The Peconic River overflowed its banks and tossed boats moored there — including a massive dredge — onto the shore, the article states.

More than 100 trees fell at Riverhead Cemetery and buildings like the Suffolk County Historical Society, the county courthouse, the elementary school on Roanoke Avenue and the high school on Pulaski Street were damaged, according to the article.

A group of “Riverhead lads” also managed to save the life of a woman trying to row across inundated Westhampton Beach, the newspaper reported.

In a special edition filed one week after the disaster, the County Review reported that at Old Steeple Church in Aquebogue the eponymous steeple was lost and a hole was punched through the roof. The church was left a “sorry looking spectacle,” the article states.

On Roanoke Avenue, barns, sheds and garages were blown down and some residents were still without water or electricity one week after the storm.

Along Sound Avenue, fruit was stripped from trees and the belfry and spire of Sound Avenue Hall were knocked down.

Ms. Campbell, now 80, recalled the damage she saw in her neighborhood after she returned home safely with a friend’s parent and the storm had fully passed. She was devastated to find that her favorite maple tree had been struck down by lightning. The tree had symbolized stability to her young mind, Ms. Campbell said.

It took until her teenage years for her to get over her fear of storms, she said.

Mr. Tomaszewski’s family was lucky; their Calverton farm suffered practically no damage in the hurricane.

“It was more the people by the bay. They got hit hard,” he said.

John Yakaboski, who recently turned 100, also recalled the substantial destruction the Express wreaked on the East End.

“That was a bad one,” he said in a brief interview from his Calverton home. “A couple weeks later we took a ride to Westhampton Beach; the seaweed was 20 feet high on the telephone pole.”

A private study done by a risk management company in 2008 showed the storm brought unparalleled destruction to the East End. The damage was equivalent to an F3 tornado, according to the study.

The storm caused $620 million in damage at the time, Mr. Stark said, or roughly $18 billion today. He added that if the 1938 hurricane hit today, it would cause an estimated $41 billion in damage.

•

Ten times more people were killed by the Long Island Express than by Sandy.

Last year’s storm brought winds near 80 mph, but Mr. Stark said Sandy’s winds stayed below hurricane force across most of Long Island.

The storm of 1938, by comparison, had sustained winds 20 to 30 mph stronger than Sandy’s most powerful gust.

And Sandy’s historic surge that swamped downtown Riverhead was still at least three feet lower than the tide brought in by the 1938 storm.

Meteorologist Stephanie Dunten at the National Weather Service station in Taunton, Mass., said that while other storms may share similar wind speed, storm surge or pressure readings, no other hurricane in the region’s recorded history has combined the different elements to create such a powerful storm.

“All the different storms have bits and pieces of it, but this one has everything,” she said. “It just baffles me.”

Weather experts say the historic nature of the 1938 hurricane’s power means few storms can match the destruction of the Long Island Express.

But storms like Sandy prove that the threat — however small — of a powerful hurricane always looms.