Real Estate: Invasive vine may have met its match

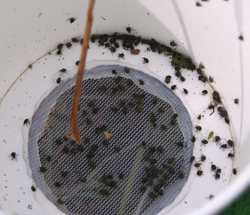

No one is declaring victory just yet, but the man-versus-nature war on what has come to be known as the mile-a-minute vine has been joined. The invasive vine has a predator, experts have found, and it comes in the form of the stem-boring black weevil.

Although he’s taking a cautiously optimistic approach, Cornell Cooperative Extension scientist Dr. Andy Senesac says there’s reason to hope that over the course of several years, the plant could be eradicated

“We’re encouraged, but we can’t be throwing any parades as far as success,” he said.

For the past two years, CCE scientists have been running test programs using the weevil on the North and South forks. The protocol for releasing the weevil was developed by a professor at the University of Delaware and the weevils are being distributed without cost by the Phillip Alampi Beneficial Insects Laboratory in Trenton, N.J., where they are being raised.

While the weevils may not be as prolific as their prey, early tests are promising that the insects will steadily eat away the invasive species and eventually wipe it out without damaging other plants that grow alongside it.

The hope is that as mile-a-minute dies off, the weevils themselves will also die off, Dr. Senesac said.

Persicaria perfoliata, as mile-a-minute is properly know, grows up to six inches a day when conditions are right. Also known as “the kudzu of the north,” it easily overmatches native species. It blocks other plants from sunlight, stopping their ability to photosynthesize, which will eventually kill them. Mile-a-minute devastates the natural ecology on a wide scale, stopping the regeneration of forests and woods and doing damage to a community’s economy.

And being an annual, with a generous amount of seeds, it’s a recurring nightmare for homeowners, gardeners and farmers.

“If you look around now, you might think, ‘Oh, it all died. But it’s not over; it will be back the next year,” said Roxanne Zimmer of Peconic, a volunteer at Cornell. “Because it’s an annual, all those beautiful blue berries will seed and reseed. And, of course, the birds and insects will carry it around as well. It doesn’t really poke its head up until June or July. And July is when you start to notice it again.”

Ms. Zimmer said the vine has a unique feature that she described as a “curved barb that allows it to grab.”

“That’s what makes it so vicious,” Ms. Zimmer said. “It can hook onto a limb or tree and then the next barb will hook on and then it just continues to grow up and out.”

According to research compiled by the University of Delaware, mile-a-minute is an Asian vine introduced to the United States in the mid-1930s at a nursery in Pennsylvania, where it was mixed with holly seeds imported from Japan. Deceptively beautiful, not only for its vibrant green color, its leaves are delicate triangles, almost heart-shaped, and its berries, when ripe, are bluish-purple. The vine has now made its home in 12 mid-Atlantic and Northeastern states, extending west to Ohio, south to the Carolinas and north to Massachusetts.

But designing and managing programs to put the weevil to work is no easy process, Dr. Senesac said.

For the dozen states experimenting with weevils, there’s a two-step approval process. It starts with the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Once a permit is received from APHIS, those in New York have to apply to the state Department of Environmental Conservation for a permit to deploy the weevils. The entire process takes about six months, Dr. Senesac said.

He generally begins the application process in October with the aim of deploying the tiny critters, which are twice the size of the head of a pin, in test areas in late April or May.

In the two years that test programs have been operated, there’s a positive indication that the weevils move beyond the point where they are originally deployed. There has also been some evidence of weevils arriving on Long Island on their own from other locations, Dr. Senesac said.

He cautioned that people whose property is overrun with mile-a-minute not pull it out at the roots at this time of year. It will die out during the winter, and early next spring would be the best time for property owners to destroy new plants, pulling them out at their roots, before they’re able to take hold.

Cornell Cooperative Extension has plans to get information to residents in early spring about how to identify the weed.

Dan Fokine, a volunteer organizer for Shelter Island Vine Busters, an awareness group, said mile-a-minute is relatively new to that island and the East End. He first saw it a couple of years ago.

“Once it hit the ground it really took off,” Mr. Fokine said.

If a neighbor has mile-a-minute, that neighbor should be approached about removing it, he advised.

He compared rooting out the vine with fighting terrorism. “You have to take the fight to it,” he said, “You just can’t fight them on your own turf.”

With Michael White