Editorial: No town should be left behind in CPF program

One of the last words any taxpayer wants to hear an elected official say is “bankrupt.”

But that’s how Riverhead Town Supervisor Sean Walter describes the town’s Community Preservation Fund. Luckily, the term is not being used literally in this case, though the difference seems to be semantic: The town will be doing nothing besides paying down debt on a loan for another 16 years until it’s paid off.

SEE STORY: “CPF REVENUES UP, THOUGH FUND STILL ‘BANKRUPT,’ SUPE SAYS”

Some who support Riverhead’s previous course of action in bonding against future CPF revenues say it’s worked out well for the town. In many cases, the town bought real estate at a lower price than it could have just a few years later. But that assessment fails to calculate what could end up being an annual shortfall for over a decade, with dollars from the town’s general fund closing the gap.

It’s a sad — and unfortunately not uncommon —story of government overspending. Town leaders bonded out three separate times, only to realize after the third time that raising $6 million each year in CPF revenue will become increasingly difficult in coming years.

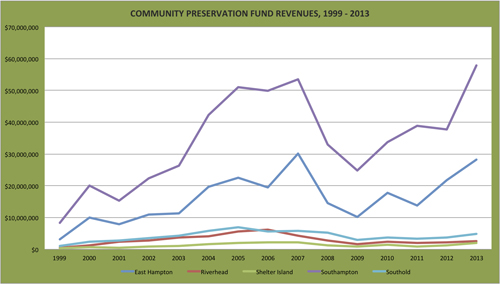

The story seems even sadder when one steps back and takes a comparative look at the revenue other towns involved in the CPF program have realized: Southampton brought in more last year alone — $57.8 million — than Riverhead has in 15 years of collecting CPF taxes ($44 million). East Hampton took in more than 10 times what Riverhead did last year.

For a program that was designed to stabilize and improve the long-term environmental health of the entire East End, one has to wonder how or why such a disparity should be allowed to exist.

Sure, real estate is more expensive in the Hamptons but not sufficiently to justify the vast differences in CPF revenue each town brings in. The median selling price of a single-family home in Southampton last quarter was only 2.5 times that of Riverhead. Yet that town brought in 22 times more CPF revenue for the year.

It’s a heavy, if not impossible, political lift. Riverhead Town overspent, and it could very well be argued that the town should reap what it has sown. But if the purpose of the fund was to preserve community character and protect the environment of the entire East End, it would only be fitting for state and local officials to make a concerted effort to see that no town finds itself in the hole in the future.

Perhaps it’s time to start talking about creating of a revenue-sharing system that would guarantee all East End towns an equal opportunity to benefit from the Community Preservation Fund.