Here’s what it’s like to be a new farmer on the East End

Abra Morawiec, owner of Feisty Acres Farm in Jamesport, didn’t grow up with dirt under her nails or farming in her blood.

Instead, the 29-year-old, whose family raised chickens in their upstate backyard, simply always had a fondness for birds and livestock. She studied English literature at Baruch College in New York City before serving in the Peace Corps from 2009 to 2011, when she was an agriculture extension agent in Mali.

“I realized that living day-to-day was sometimes a struggle,” said Ms. Morawiec, whose organic quail farm is the first in New York. “I liked farming and living a farm lifestyle. In Mali, if you didn’t farm, you didn’t eat.”

But Long Island isn’t Mali. Between the cost of land and equipment and the challenge of finding a market for her product, starting her own venture has been a learning experience, to say the least.

Ms. Morawiec is one example of a new crop of farmers who must learn as they go along.

“The biggest challenge for me was starting from the bottom, as an apprentice, and trying to figure out how can I save my money up to actually start my own enterprise,” she said. “The only way that I could possibly make that happen is by forming relationships.”

Ms. Morawiec did just that with numerous farmers on the East End, she said. But most notable were her friendships with Chris and Holly Browder of Browder’s Birds in Mattituck and Phil Barbato, owner of Biophilia Farm in Jamesport.

Ms. Morawiec rents land and barn space from Mr. Barbato and uses the Browders’ mobile processing unit to slaughter her birds.

“Especially in this part of the state, it’s tough to get a start because the land prices are so high. But on the flip side, the market is right here,” Mr. Barbato said. “So, I think it’s important that we give young and/or beginning farmers help … We want to be able to pass things on and we want things to stay healthy and wholesome like they are now.”

Chris Browder made the switch to farming with even less previous agricultural exposure than Ms. Morawiec.

In 2004, after 20 years as a banker in Manhattan, he packed up his desk, grabbed a copy of “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” and made the move to the North Fork with his wife, Holly.

The couple spent the next several years on a winding journey into a business filled with unforeseen roadblocks. To succeed as farmers without having grown up in a farming family presents a unique set of challenges, they found.

It took them six years to establish Browder’s Birds, and getting the business off the ground was far from simple.

To get started, Mr. Browder applied for an apprenticeship with Garden of Eve organic farm and market in Riverhead, where he spent a season. He raised a flock of meat birds, which he later slaughtered and sold.

Mr. Browder said that after acquiring the land, he still needed the basics — tractor, tiller, animals and more — which was a “daunting” task when it came to cost.

“It’s not like I’m sitting over here made of money,” he said. “That’s been probably the biggest challenge, just how much money it actually costs … It’s not like we’re sitting here with mountains of equipment and lots of structures and so forth. Pretty much everything we have is kind of made homemade. Even with that, it’s still very expensive.”

Dan Heston, senior manager of agricultural programs at Peconic Land Trust, said that many people entering the industry today are what he calls “second-career farmers,” like Mr. Browder. That trend has pushed the national average age for a farmer to 57. Five years ago, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the average farmer in America was 55 years old. Since 2010, the number of farmers over age 75 has risen by 30 percent and the number under age 25 has dropped by 20 percent.

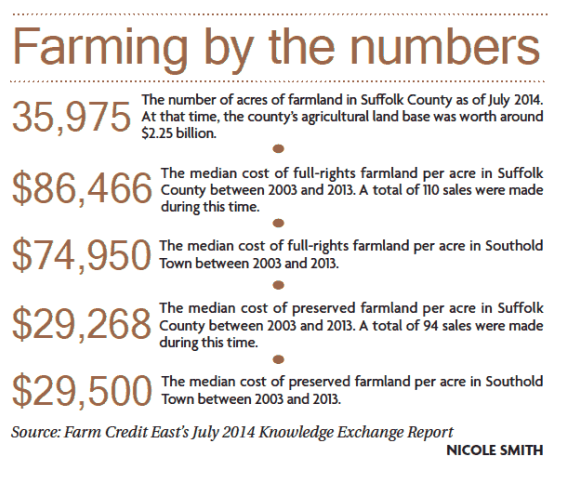

In Suffolk County, the cost of one acre of farmland starts at around $12,000 and has gone as high as $2 million, according to a 2014 study by Farm Credit East, a borrower-owned lending cooperative specifically serving the agricultural industry.

To help ease the financial strain of getting into agriculture, numerous organizations, like Farm Credit East and Peconic Land Trust, have created scholarship and grant funds specifically used to aid beginning farmers.

One related program is FarmStart, established by Farm Credit East in 2005, which will invest up to $50,000 of working capital in the operations of new farmers and cooperatives. Each beneficiary works with a FarmStart adviser who provides financial and management training throughout the term of the investment, said Bob Smith of Farm Credit East. The objective is not only to provide start-up funding, but to help new farmers establish strong business plans and solid credit records.

Farm Credit East also offers scholarships to college students interested in agriculture, pays fees associated with USDA-FSA loan guarantees, reduces interest rates for young farmers through loan guarantees and offers discounts for financial services.

Another problem beginning farmers face involves the availability of farmland, a particularly pertinent issue on the North Fork. The Peconic Land Trust has worked to fix this, Mr. Heston said, through its Farms for the Future program.

“What we do is basically provide someplace for them to be,” he said. “We have the land and some infrastructure, such as wells and fencing,” he said. “And then we also, if they want, we provide some mentoring.”

The land offered is through a preservation program established in the 1970s that sets land aside to be used strictly for agriculture, allowing it to be leased, rather than purchased, at a relatively affordable cost.

Yet another potential stumbling block can come with the business side of agriculture, which Mr. Smith said novice farmers don’t always realize plays such a big role. To help educate farmers, Farm Credit East offers classes and webinars focused on the business aspects of farming.

“It’s the combination of really being a top-notch producer, understanding your market and market challenges with competitors and being a good financial manager,” Mr. Smith said of the profession.

Understanding the market is another issue. Since Riverhead and Southold are so saturated with agriculture businesses, it can be difficult to find success. Farmers need a niche product, something they can offer that people can’t find elsewhere, Mr. Smith and others interviewed said.

The final challenge comes with no immediate solution — a lack of fundamental knowledge. Mr. Heston said that some “people don’t have the skills to farm, but they think they do.” He said there is a lot more to farming than meets the eye that people who didn’t grow up farming fail to realize. This includes how to work all the machines, how to set up an irrigation system, what equipment is necessary and more. This is the one challenge that doesn’t have a clear-cut solution. It’s nearly impossible to make up for all the lost time.

Mr. Heston said that having apprenticeships and making connections with people in the industry, however, helps with that hurdle. Ms. Morawiec, who found her success through mentorship, said more programs are needed to pair new farmers with more established ones as guides.

Despite all the hurdles a new farmer faces, interest in joining the agricultural industry remains high.

“There’s more interest now than there’s been in the last 15 years, I know that,” Mr. Heston said. “People really want to get back to their roots and grow something and do something.”

Photo caption: Farmer Abra Morawiec holds a six week-old roo (male) Cortunix at her Feisty Acres farm where she leases land from farmer Phil Barbato of Biophilia Organic Farm on Manor Lane in Jamesport Manor Lane in Jamesport. (Credit: Barbaraellen Koch)