Special Report: Ken LaValle, Mr. Longevity in the Senate

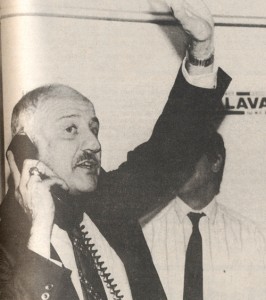

Late on the evening of Nov. 6, 1990, Senator Ken LaValle hung up the phone at his campaign headquarters in Selden and looked out at his crowd of supporters.

He had just received a concession call from his opponent that year, Sherrye Henry, a TV political talk show host who spent a whopping $500,000 to unseat the then 14-year senator.

Ms. Henry had received just 34 percent of the vote.

To this day, political pundits and newspaper scribes say the East Hampton resident, with roots in Memphis, Tenn., and New York City, put up the toughest fight against Mr. LaValle of any of the 19 opponents he faced since he first ran for office in 1976.

Yet she didn’t come close.

The election success of Mr. LaValle, 73, who come January will share the distinction of being the longest-tenured senator in New York, is nearly unparalleled among state senators in the U.S.

When Mr. LaValle is sworn in for his 19th term in January, Republican William Doyle of Vermont will be the only active state senator in the nation to have served more terms. Mr. Doyle, 86, was first elected to his post in 1968 and won a 23rd term earlier this month.

In all, six state senators across the U.S. will have been in office longer than Mr. LaValle as of January, though five of them serve in states where they have to run only once every four years. Democrat Fred Risser of Wisconsin is the longest-tenured state senator in the U.S., having been first elected in 1962 after serving six years in the Wisconsin State Assembly.

That means that of the 1,971 state senators serving in this country next year, only Mr. Doyle, Mr. Risser, Democrat Chuck Colgan of Virginia, Democrat Douglas Henry of Vermont and Democrats Norman Stone and Mike Miller of Maryland have been in office longer than Mr. LaValle.

They tried, they lost

“I certainly was circumspect about my chances to win, but there was a part of me at that time that thought it might be possible.”

— Ira Costell, LaValle opponent, 1986

It’s been 100 years since a Democrat was elected to represent New York’s 1st Senatorial District. Thomas H. O’Keefe of Oyster Bay won the post by 2,355 votes over Republican George L. Thompson on Nov. 5, 1912. The anti-Tammany Democrat was one of just 12 senators in 1913 to vote against the impeachment of Governor William Sulzer, who remains the only New York State governor ever to be impeached.

Mr. O’Keefe did not seek re-election in 1914 and was replaced by his opponent in the previous election.

Mr. Thompson spent the next 26 years in office, beginning an era of Republican domination that has continued through this month’s re-election of Mr. LaValle. The senator’s most recent opponent, Bridget Fleming of Sag Harbor, who gained just under 40 percent of the vote, actually fared better than any other opponent in a LaValle re-election bid.

In the past century, only eight Democrats have received a higher percentage of the 1st District vote than Ms. Fleming did this year.

One of those candidates was longtime Stony Brook University physicist Barry McCoy, who received 42.55 percent of the vote in 1976, the year Mr. LaValle was first elected. Mr. McCoy, who Mr. LaValle called the “greatest tactician” he’s ever faced, made a name for himself in 1974, at the height of the Watergate Scandal, when he led the first Democratic takeover of the Brookhaven Town Board, Mr. LaValle said.

“It was like I was playing chess with him,” the senator recalled in an interview this week. “He’d make a remark [at a campaign event] like ‘I’ve got 200 volunteers working for me.’ I’d say to my staff, ‘We need to have 201 volunteers.’ ”

Mr. LaValle was 37 years old when he first sought public office in 1976. A teacher and school administrator in the Middle Country School District in the 1960s, he went on to serve as an aide to his predecessor, Leon Giuffreda. In that capacity, Mr. LaValle served as executive director of the Senate committee on education and the joint legislative committee on mental and physical handicaps.

In the Suffolk Times’ 1976 voter guide, Mr. LaValle said the key issue for the five East End Towns — the 1st District at the time also included all of Brookhaven Town except Patchogue and Blue Point — was to “maintain integrity over zoning so that the character of the area will be maintained.”

Mr. McCoy, who secured the Democratic nomination through a primary after “Doc” Menendez of Riverhead was the choice coming out of the convention, stated in the same guide that his key issue was to prevent the construction of a Cross Sound Bridge connecting Long Island to Connecticut.

Heralded largely for his experience in Albany, Mr. LaValle quickly emerged as the favorite in the race and never lost his edge in a year that saw Democrat Jimmy Carter elected president and Democrat Otis Pike re-elected to Congress in New York’s 1st District. Mr. LaValle enjoyed particular success in Southold and Southampton towns, where he received a 5,200-vote advantage over his opponent.

He quickly increased his profile on the East End by introducing the Farmland Preservation Act in his first term. The landmark legislation called for state and local governments to each pay half the cost of buying and preserving farmland. In return for accepting fair-market value for land, a farmer would agree to include a deed restricting the land from being sold for anything but farming.

By the time his first bid for re-election rolled around in 1978, Mr. LaValle had become so popular he received 5,000 more votes than he did in his first election bid, despite the fact that 1978 was a non-presidential year in which 1st District voter turnout dropped 20 percent.

It would be another 12 years before a LaValle opponent would receive more than 30 percent of the vote.

The senator has outgained his opponents by such large margins that many have wondered if Democrats have even tried most years to unseat him.

In a recent interview, even Ms. Henry, widely regarded as his most legitimate challenger, said she believed this.

“A lot of years the candidate has been nothing more than a name on a ballot,” Ms. Henry said.

It’s a point Mr. LaValle takes exception to.

In 1980, he defeated Robert Gottlieb by the fifth-largest margin over anyone he’s ever defeated, yet he says Mr. Gottlieb, a former Suffolk County assistant district attorney, put up a nasty fight.

“He was the most pugnacious opponent I ever faced,” Mr. LaValle said of Mr. Gottlieb. “If I said it’s raining outside, he’d say ‘How do you know that?’ ”

Even the man who received the fewest votes of all against Mr. LaValle, Ira Costell of Port Jefferson Station, said he put his best foot forward. Mr. Costell, then a 28-year-old who one year earlier had run an unsuccessful campaign for Brookhaven Town Board but fared well along the North Shore, received just 19,013 votes in 1986, a low turnout year. An anti-Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant candidate, he secured just 25.9 percent of the vote despite capturing the endorsement of the historically conservative Suffolk Life newspaper.

“It’s actually kind of depressing I got the least votes,” Mr. Costell said with a laugh. “But it was definitely a daunting task.”

The chosen one

“I didn’t just lose a campaign that year, I lost my reputation.”

Sherrye Henry, LaValle opponent, 1990

Sherrye Henry was a popular New York City television and radio personality in the 1970s and ’80s who claims in her 1994 book “The Deep Divide” to have at one time hosted the city’s most listened-to radio interview program.

The first woman in the country to broadcast television editorials, Ms. Henry was best known as a staunch feminist. A 1971 print advertisement for her CBS morning television show “Woman!,” vowed to promote the issues that matter most to women, not just give “cooking lessons” or “sewing tips.”

In 1990, Governor Mario Cuomo asked former vice presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro to recruit women to run in 14 districts across New York where Democrats believed a campaign on feminist issues could help the party gain a majority in a state Senate where Republicans held just a four-seat advantage. The strategy came on the heels of a U.S. Supreme Court decision that would have put abortion rights in the hands of state legislators.

Ms. Ferraro tapped Ms. Henry, who split her time between East Hampton and Manhattan, to run in the 1st District. A Yale graduate, and no stranger to politics, Ms. Henry had connections to the Kennedys and her former husband served as commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission during John F. Kennedy’s presidency.

Most importantly to Ms. Ferraro and Gov. Cuomo, Ms. Henry was a vocal pro-choice proponent whose media background could help her and 1st District Assembly candidate Linda Bird Francke secure prime television interviews.

“They even appeared on the Ted Koppel Show,” Mr. LaValle recalled.

Ms. Henry’s growing profile — Superman himself, Christopher Reeve, came out to support her — and her contrasting style from Mr. LaValle’s had his campaign worried.

Then there was the money being spent.

To this day, no LaValle opponent’s campaign committee has spent more than the half-million dollars spent by Ms. Henry. Only Regina Calcaterra of New Suffolk came close in 2010, spending nearly $400,000 before her bid was cut short due to residency restrictions. By comparison, Ms. Fleming’s run this year cost less than half of what Ms. Henry’s campaign spent 22 years earlier.

“They bought spots during the World Series,” Mr. LaValle said — an expensive buy in a year where the home team Yankees represented the American League.

One frequently aired radio and television advertisement, according to a 1990 New York Times story, criticized Mr. LaValle for voting “against our right to choose.”

“He’s just not listening to us,” the ad suggested to women voters.

It was a high-energy campaign complete with debates both Mr. LaValle and Ms. Henry described as spirited. Both candidates were forced to knock on thousands of doors across the East End. At one point polling numbers suggested the candidates were neck and neck, a Henry campaign staffer recalled.

Then things took a turn for the worse for the challenger.

In October, Ms. Henry’s campaign issued a mailer that ripped Mr. LaValle for poor attendance in the Senate, stating he had missed votes on 119 bills that year. They were working from information the state Democratic Committee had given them, but that information failed to reflect that nearly all of those votes occurred over a brief stretch during which Mr. LaValle was visiting his gravely ill father in a Long Island hospital and later attending to the details of his funeral.

That’s when the LaValle campaign took off the gloves.

The senator began to make frequent radio and television appearances decrying Ms. Henry’s “lack of accuracy and sensitivity,” according to the Nov. 8, 1990, issue of the Riverhead News-Review. Eventually, Ms. Henry offered a public apology.

Looking back, Ms. Henry said in an interview earlier this month that two tactics employed by the LaValle campaign still bother her to this day.

One was a print advertisement she said was created by artists at Suffolk Life that described her as “a woman of low moral character,” a statement she said was also made in Republican radio spots that year.

Ms. Henry’s other key beef with the LaValle campaign was a claim she said the senator made at the end of a televised debate that stated Ms. Henry had voted twice in the 1984 presidential election, at both her home district in East Hampton and her previous polling place in Manhattan. Ms. Henry said she voted only in East Hampton that year but, due to a Board of Elections oversight, her name still appeared on the voter log in the city.

“Like I was going to go from the Hamptons to the city for one extra vote in Mondale’s losing campaign,” Ms. Henry said. “At that point, the election had completely turned.”

By the time election night rolled around, Ms. Henry said she knew she had lost the campaign, she just didn’t realize by how much. The final tally was 52,306 votes for Mr. LaValle, to just 27,353 for Ms. Henry.

“I will remember that race in my grave,” Ms. Henry said.

As a victorious Mr. LaValle hung up the phone that night at campaign headquarters, he uttered one sentence to his teary-eyed family members and campaign staffers.

“Well, this victory was for pop,” he said.

How he does it

“He has a remarkable ability to listen.”

John Jay LaValle, Suffolk County

Republican chairman

Senator LaValle often references a thick black binder he keeps with him on the Senate floor. Indexed in the bulging book is community input on key issues. If a constituent calls his office to voice support or opposition to a particular piece of legislation, a LaValle staffer will log the call, which makes its way into the book. Newspaper columns and editorials also get clipped and inserted.

But don’t expect to see Mr. LaValle sipping a cup of coffee and reading the latest issue of the Port Jefferson Times Record at his Port Jefferson home during campaign season.

“I don’t ever open the local papers during a campaign,” he said. “And I only listen to Connecticut radio stations.”

He says that tactic keeps his mind clear of claims made in political advertisements.

It’s all part of a larger philosophy the senator has developed that he says keeps him from looking back on the past. Because of this mind-set, he claims he doesn’t regret a single vote he’s ever cast.

“I talk to other senators who tell me they don’t sleep the night before a big vote,” he said. “I’ve had very few, if any, votes where I had to think about it at the last minute.”

He says that he votes based largely on constituent feedback given to him and his staff. If public input is split on an issue — he said he voted against gay marriage last year even though the communication he received was near 50/50 — he uses campaign promises he made and his own intuition to determine how to vote.

“I ran on civil unions [in 2010],” he said of his vote against the bill that ultimately legalized gay marriage. “I wasn’t going back on that.”

It’s the issues, Mr. LaValle said, that keep him interested in his job. He admits that when he first ran in 1976, he told reporters he would not remain in the position for more than 10 years.

He almost stayed true to that promise. In early 1986, Republican leaders made a strong push for him to run a primary against Congressman William Carney. It’s one of three times he’s been asked to seek higher office.

But by April 1986, he had withdrawn his name from consideration.

“I never really wanted to go to Washington,” Mr. LaValle said. “And looking at Washington today, I’m so glad I didn’t.”

Ultimately, he said his decisions to seek re-election to the Senate have been based largely on a desire to follow legislation he is working on to the finish line. This year, he said, the decade-old negotiation to unite Southampton Hospital with the Stony Brook University system was his single biggest reason to stay in office. As it turns out, a deal was struck late in his 2012 campaign. He said he is looking to expand on his goal to improve health care on the East End by also bringing both Peconic Bay Medical Center and Eastern Long Island Hospital into the Stony Brook system. He said this week that meetings have already been scheduled with officials at both hospitals.

The face-to-face meeting is where LaValle supporters say the senator excels politically.

“He’s everywhere,” said county GOP chairman John Jay LaValle, a former Brookhaven Town Supervisor and a cousin of the senator. “A lot of politicians win an election or two and they get lazy. Ken has never let up. He has a presence at every major event and he has a passion for learning and a passion for listening.”

Even his critics and former opponents acknowledge that it’s hard to miss Mr. LaValle and his trademark red baseball cap at events throughout the district, even if they disagree with his politics.

“Listen, he’s affable and gentlemanly and an overall nice guy,” said Mr. Costell, his 1986 opponent. “But I think a lot of his success has come from the clout he’s built through decades worth of political favors. He’s definitely a go-along-to-get-along kind of guy.

“As a person, he’s a fine individual, but for the great length that he’s been in office I’m hard pressed to come up with that trademark legislation of his that’s had a dramatic impact,” Mr. Costell said.

Of course, Mr. LaValle disagrees. He frequently points to his sponsorship of the Pine Barrens Protection Act of 1993 as his signature bill. As a longtime chairman of the Senate higher education committee, he also lists the expansion of Stony Brook University, where the $22 million football stadium bears his name, among his career highlights.

“My desire is to see Stony Brook move up the ranks of national universities,” he said.

And to that end, he says he has no plan to quit, even as he enters his first year as the senior member of the Senate — a distinction he will share with 80-year-old Sen. Hugh Farley of Schenectady, who was also first elected in 1976.

He said he doesn’t plan to slow down, either.

“It all goes back to something my father would always say when I was playing sports in my youth,” Mr. LaValle said. “He’d say ‘I don’t care if you win or lose, just don’t get out-hustled.’ ”