How a biologist found WWII-era explosives unearthed by Sandy

Gardiners Point Island looked different to coastal biologist Curt Kessler as he walked around the remains of Fort Tyler, a relic of the Spanish-American War.

As Mr. Kessler, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employee, walked the small island with coworkers on July 5, counting bird nests and searching for signs of bird activity, he noticed that large concrete blocks had been moved across the island as if dragged by a giant. The sands had shifted in places.

“Sandy had really washed over the island and changed it a lot,” he said of the late October storm.

As Mr. Kessler walked along the waterline, he began to notice small metal fragments washed up along the shore.

Then he saw a strange shape just below the surface — an oblong piece of rusted metal about a foot long, nestled among a group of smoothed rocks.

He stopped. This was different from the other metal scraps he’d seen.

Mr. Kessler had served in the U.S. Navy for four years and spent time recently on the island of Saipan — a World War II battle site littered with munitions — while working with endangered species. He instantly recognized what he was looking at.

“The fins kind of gave it away,” Mr. Kessler said.

Mr. Kessler was standing only a few feet away from an unexploded bomb.

•

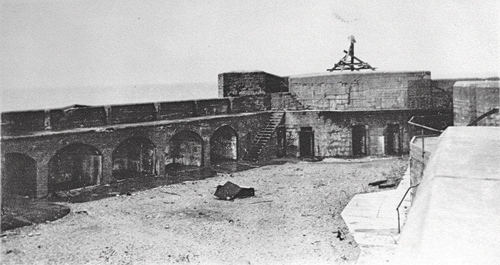

Better known as “The Ruins,” the rocky 500-foot-long Gardiners Point Island has a surprising history for such a tiny spot.

It was once the far end of a thin spit of sand attached to Gardiners Island. A lighthouse stood there in the mid-1800s, but by the 1890s, the island’s instability caused the government to consider relocating the lighthouse.

It never got the chance. In 1894, a storm damaged the lighthouse, which was left to fall into the sea.

By that time, storms had cut the peninsula off from Gardiners Island, turning it into Gardiners Point Island.

The island was transferred to the War Department, the precursor of the Department of Defense, four years later. Fort Tyler — named after President John Tyler — was built there to protect New York waterways during the Spanish-American War. Fort Terry on Plum Island was built for the same purpose.

Guns were installed in concrete parapets at Fort Tyler, but it saw no action and was closed in the 1920s, making it a prime target practice site for the U.S. military.

“After the Spanish-American War, they threw all kinds of stuff at it,” said Ned Smith, a librarian with the Suffolk County Historical Society.

In the summer of 1936, the U.S. Army used the abandoned fort as target practice for bombers from the Ninth Bombardment Group out of Mitchel Field in Mattituck, according to a report in The Watchman newspaper that year.

The military used 100-pound bombs that were mostly filled with sand and water, with a pound of black powder to “create a visible puff of smoke for observers,” the article states.

Though military officials assured that the bombs were safe, then-Southold Supervisor S. Wentworth Horton and East Hampton Town Supervisor Perry Duryea protested the training. Bluefish fishermen also complained about the military training, since Gardiners Point Island had become a prime fishing spot.

About a week after the training began, a well-known restaurateur from Brooklyn “narrowly escaped death” when U.S. Army planes dropped a shower of bombs over Gardiners Bay, where he was sailing with six friends, according to a Watchman article from August 1936.

Some of the bombs landed within 50 feet of his boat, according to the article.

Two years later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared the island a national bird refuge, but about a decade later the old fort — having now adopted the nickname “The Ruins” — was once again put in the crosshairs.

This time, the U.S. Navy targeted the island, dropping smaller bombs that weighed two pounds and four ounces from naval aircraft, according to a 1949 article in the County Review newspaper. At the time, the Long Island Fishermen’s Association reported one fisherman had 100 lobster pots annihilated by the bombing.

Once again, the East End town supervisors slammed the bombing training. In October 1949, Southold Town Supervisor Norman Klipp sponsored a resolution that said the target practice would be a “potential danger to life, limb and property” and would ruin the fishing stock.

The Navy ignored the complaints and went ahead with the bombing, sending a note to the Board of Supervisors a month later stating that the bombings posed no danger to boaters or fishermen.

The island, and what remains of Fort Tyler, were eventually handed over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as excess federal property.

The site has been used as a bird sanctuary for nesting common and roseate terns, small seabirds that feed on local fish. But while the ruins may be an ideal home for birds, it’s no place for humans.

There’s a danger that unexploded munitions could still be hidden under the sand, authorities say.

•

Mr. Kessler had just completed unexploded ordnance training, so he knew what to do the moment he saw the rusty bomb: recognize, retreat, report, record.

“Basically, don’t touch them,” he said. “You’re never sure. Even if it looks like a dummy round it could [explode].”

Mr. Kessler took a photo of the munitions lurking under the water and ran back to warn his friends and report the ordnance to his superiors.

Despite the bomb nearby, Mr. Kessler said he and the three other biologists on the island never panicked. The chance that a bomb could wash ashore had always been present, he said.

“Nobody was that surprised,” Mr. Kessler said.

But the Suffolk County Emergency Services Unit was.

“Once in a while we’ll find things outside, but this was unique,” said Lt. Kevin Burke, commanding officer of the emergency services unit.

He said the recently discovered ordnance wasn’t “easily found. If you weren’t looking for it, you might not have seen it.”

The county police bomb squad was called to the scene about 12:50 p.m., authorities said.

Southold and Riverhead Town police had helped set up a 300- to 400-foot perimeter around the area. Members of the bomb squad were ferried to the island by the East Hampton Marine Patrol, jumping off the boat into knee-deep water to prevent the vessel from running aground, Lt. Burke said.

The East End Marine Task Force’s Vessel 41 — the unit’s newest ship, designed to respond to nuclear, chemical or biological attacks or accidents — was also activated for the operation, authorities said.

Lt. Burke said the bomb squad sometimes returns unexploded ordnance to the military if the bombs are stable and in good condition. The weapons found on Gardiners Point Island — two eight-inch aerial bombs — were anything but.

“A lot of times when they’re exposed to the elements the explosive powder will leach out,” Lt. Burke said. The bomb squad would be taking no chances.

They hooked up the top two bombs and detonated, but the bombs didn’t blow up, Lt. Burke said. Those bombs had lost their explosive charges and were detonated harmlessly.

But when emergency personnel returned to the scene they found a third aerial bomb hidden beneath the first two. Once again, the bomb squad detonated a charge.

But this time, the bomb exploded, blowing a crater in the shoreline.

“That would have done serious damage,” Lt. Burke said. “If someone had been there they would have been killed.”

No one was hurt in the operation.

For years, the U.S. Coast Guard has enforced a 500-yard hazardous zone around the island where boaters cannot sail or dock. Authorities said this month’s discovery of an unexploded bomb was proof of why boaters should stay far away.

Michelle Potter, a refuge manager for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said the government knew there was “the possibility” of potentially dangerous munitions to be uncovered.

“It’s not a place for the public to stop and scope out,” Ms. Potter said.