Ukrainian church praying for peace in home country

Every morning for the past few months, parishioners at St. John the Baptist Ukrainian Catholic Church in Riverhead have gone through the same nerve-wracking ritual.

About 50 families who attend the parish — many of them immigrants or the children of émigrés from the western parts of Ukraine — wake up and check their email for messages from family members still in the country.

They go online to check Ukrainian news telecasts, which report the latest moves by Russia to take control of Crimea, a peninsula on the southern edge of the country that borders Russia to the east.

They pray that the instability now threatening their home country’s safety will end without war.

“All of us here — our parish, our families, all over — are very concerned about what’s going on,” Father Roman Malyarchuk, pastor at the church for more than two years, said through a translator. “Ukraine has taken the first hit, but this is becoming a problem for all of Eastern Europe, all of Europe, all of the world.”

The conflict began last November as a protest against corruption in the Ukrainian government and then-Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to align himself more closely with Russia. After a peace agreement was reached with opposition forces in February, Mr. Yanukovych fled the country. The new transition government has since seen Russian military forces march into Crimea, supposedly to protect ethnic Russians living there.

But the motives of these forces — and the country sending them in — have been criticized worldwide, including by congregants of St. John the Baptist Ukrainian Catholic Church.

“At first it was a great euphoria, that finally Ukrainians are standing up for themselves,” said parishioner George Rakowsky. “Now, it’s anxiety and worry about the future.”

On Sunday, a Crimean referendum vote overwhelmingly supported joining Russia. Western and Ukrainian authorities have declared the vote illegitimate, saying it was rigged under the auspices of occupying Russian military forces in the peninsula. That same day, Riverhead parishioners celebrated the 200th anniversary of the birth of Taras Shevchenko, a revered poet, painter and national icon who was imprisoned and exiled by the Russian monarchy for his inflammatory writings against Emperor Nicholas I.

“It’s interesting that his poetry is so relevant today,” said Mr. Rakowsky, who fled Ukraine with his parents as refugees when he was 10 years old. “He ranted against the czar and now we have another ‘czar’ threatening Ukraine.”

On Sunday, the congregation prayed for good news: an end to the conflict.

But on Tuesday, they were met with more disappointment when Russian President Vladimir Putin, in a speech before the Russian political elite, declared that the Crimean territory was now a part of Russia — a move quickly backed by the Russian legislature. Reports poured in from home, said parishioner Irene Andreadis, holding print-outs of the emails.

One email from her brother-in-law, Petro Matiaszek, who lives in Ukraine’s capital city of Kiev, read: “The situation here remains very tense … Ukrainians want to live peacefully in their own democratic country, not under a Russian dictatorship. We’re taking it day-by-day. Our suitcases are ready in case we have to flee westward.”

Ms. Andreadis’ American-born sister is also working in Kiev, she said. The couple’s apartment overlooks Independence Square, where dozens of protesters were killed during clashes with riot police during the months-long protests.

“It’s very agonizing, everything that’s happening,” Father Malyarchuk said. “We pray for peace and we put our trust in God.”

According to the church’s website, the Ukrainian population first made its way to the East End in the late 1800s, led by a group of immigrants from Halychyna, a village near the Polish border. The congregation started out as a gathering place in one member’s dining room on Pond View Road and. in 1924, purchased the land across the street, where the church currently sits.

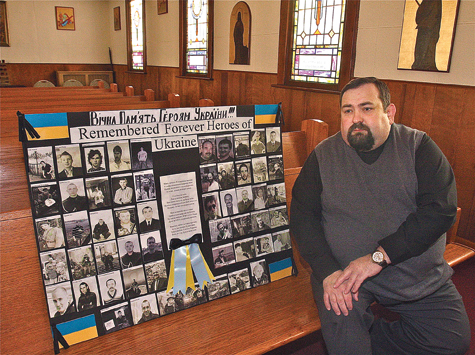

The church has now raised a Ukrainian flag beneath the American one on its flagpole outside. Flowers were laid there in memory of the hundreds of people hurt in the crisis. Inside, set behind a row of candles, the faces of those killed during the violent protests stare out from a poster board honoring the “Remembered Forever Heroes of Ukraine.”

But honoring the dead isn’t enough, parishioners say. Ten people from the church demonstrated with a group in front of the White House in Washington, D.C., on March 6 to raise awareness of the growing crisis and demand that stronger action be taken against Russia. Local Ukrainians have also protested in New York City against what they see as American inaction.

“We’re grateful to Obama’s administration for marshaling the forces and doing the talk, but you have to support it,” Ms. Andreadis said. “They’ve been talking about doing sanctions. These things should have been done immediately.”

Returning a missile defense system to Ukraine would be a way to deter further Russian aggression, she suggested.

Father Malyarchuk said the crisis sets a precedent that international law can be flouted.

“The framework that controls international relations … has now been broken,” he said. “So any dictator can do the same.”

In Father Malyarchuk’s home behind the church Tuesday afternoon, tucked among paintings of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, a computer continually blared the latest news from Ukrainian television Channel 5. Father Malyarchuk turned down the volume for a quick brunch with Mr. Rakowsky and Ms. Andreadis, who couldn’t refuse his hospitality. It was a short break for the pastor and his parishioners, who will soon go back to sharing videos of the crisis with friends in the U.S. and contacting relatives abroad.

The three sipped coffee, chatted and sampled Father Malyarchuk’s Ukrainian chocolates, a comforting reminder of home — and hope.