New map shows hypoxia ‘dead zones’ in North Fork waters

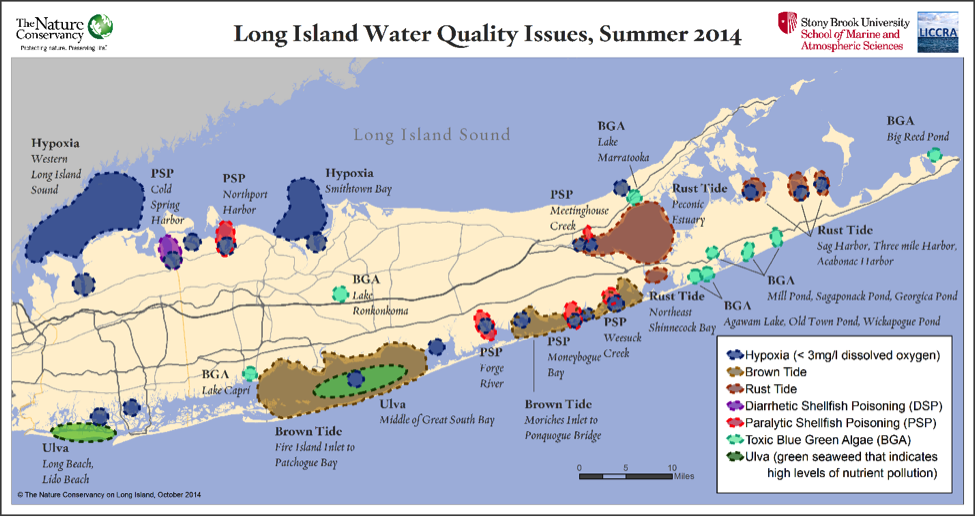

Researchers from Stony Brook University and The Nature Conservancy released a map last week that depicts the location and breadth of water quality problems, such as brown tide and hypoxia, that cropped up around Long Island this past year.

While the experts noted the cool summer helped ward off the potential for widespread algal blooms, the blooms weren’t the only cause for concern in 2014.

And, the issues were widespread, ranging Long Island Sound waters near the Bronx and Queens, to Mattituck and Montauk.

The map highlights the presence of rust tides in the western Peconics, paralytic shellfish poisoning in Meetinghouse Creek in Aquebogue, and toxic blue-green algae in Mattituck’s Lake Marratooka, among others.

“While we have seen these events individually in the past, the confluence of all of these events in all these places across Long Island in a single season is a troubling development,” said Christopher Gobler, a Stony Brook professor who unveiled the map at a press event last Wednesday at the Stony Brook/Southampton campus.

Researchers said the most troubling of findings was the number of areas suffering from hypoxia, “dead zones” found deficient in the amount of oxygen needed for aquatic life to survive.

Locally, the phenomenon was found in two areas in the western Peconics and Mattituck Inlet, as well as several areas across the South Shore.

According to the state Department of Environmental Conservation, for fish to survive, marine waters should never go below 3 mg of dissolved oxygen per liter.

More than 20 of the 30 locations across Long Island that researchers tested regularly showed oxygen levels far below the 3 mg limit, at times recording no oxygen at all, Mr. Gobler said.

“Seventy percent of the sites sampled did not meet this criteria,” Mr. Gobler said. “The data reveals that something must change.”

The new data became available thanks to 30 new data recorders, which cost Stony Brook about $1,000 apiece. The devices, when submerged, take readings throughout the day and night, giving researchers a full week’s worth of time-stamped information once downloaded, Mr. Gobler said.

And while oxygen levels in certain areas seemed fine during the day, levels plummeted at night, as the sun was not out to promote photosynthesis of underwater vegetation, researchers found.

Mr. Clapp said the low oxygen levels are especially dangerous to shellfish, including clams and scallops, as well as smaller bait fish that may not be able to swim and leave areas quickly.

“Long Islanders should take this as a call to arms,” said Maureen Dolan Murphy, an executive programs manager of Citizen’s Campaign for the Environment who was also at the press conference. “Our bays are dying and the science clearly shows us why.”

Mr. Gobler said “all of these events can be traced back to the rising levels of nitrogen coming from land and entering Long Island’s surface waters.”

Mr. Clapp said waiting to address nitrogen issues “is no longer an option,” explaining it could take decades for restoration to occur, even if issues are addressed now.