Guest Column: Living life like a Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone is for sale. Not that I have looked at it in years. It was and is a magazine primarily for young men. There was a time, though, when I read it religiously. On my way to the stacks in my college library, I was often waylaid at the periodicals section for hours as I studied the magazine. The gossip (James Taylor and Joni Mitchell broke up!) the record reviews and the political coverage informed my point of view and gave me entree to a much cooler world than the one at my women’s college, where we still had mixers with the nearby men’s colleges and guessing which dorm mates were still virgins was a popular pastime. When I landed a job at the magazine in 1976, it was transformative.

Initially, I worked in the photo department, keeping a wall of filing cabinets up to date with the daily blitz of record company PR shots and concert pictures dropped off by hopeful young photographers. Annie Leibovitz, the staff photographer with a whirlwind presence, only added to the allure. Stopping off in the photo department between her travels on the road with various groups (The Allman Brothers! The Stones! Fleetwood Mac!), her unfettered access and art school training produced astonishing images. Somehow, just looking at her pictures made me feel part of the whole wild and woolly youth culture. I was privy to photos of my favorite artists — mostly young men — captured backstage, off-duty and sometimes half-naked.

The office was on the top floor of an old brick warehouse, south of Market Street in San Francisco, a seedy ungentrified area. The staff, uniformly young, was a motley bunch, some with names that strained the imagination. I was too intimidated to ask if Bond Francisco, Jeanne Jambu or Pinky Black were their real names or some drug-induced inventions. Reputations preceded many, like writer Charlie Perry, who was UC/Berkeley roommates with the Grateful Dead’s acid cooker, Owsley Stanley, and played midwife at the birth of psychedelia. There was plenty of outrageous behavior: writer Chris Hodenfeld driving his Harley into the elevator to park it at the reception desk; the friendly guy who walked around the office selling pot brownies and cookies; the deadline antics of Hunter Thompson, whose endless stories pouring out of the mojo (a hog-sized telecopier machine) kept us up all night to finalize the pages for the printer. Those of us who actually produced the magazine — copy editors, fact-checkers, paste-up artists, designers, photo lab technicians — took pride in getting our jobs done and done well, knowing that the magic fairy dust of rock ’n’ roll was all around us.

My next job was in the production department, as assistant to the newly hired manager, a young woman from LA only a couple of years older than myself.

Mary was impressive in that she was not at all outrageous, quite the opposite in her calm and orderly behavior. She, like me, was a product of Catholic schools and we soon began dressing in what could be described as uniforms — not our old wool plaid jumpers but pretty designer overalls, loose fitting, in soft creamy cotton. She became a mentor, teaching me all the intricacies of marking up galleys for the typesetter and a new language of picas, points, leading, drop caps, justified type, rag right, caps with small caps. I was falling in love with type and started collecting old specimen books with beautiful old French, British and Italian fonts, often shown with ornamental flourishes and the oddly-named dingbats. It was all an arsenal to create beautiful pages and I was an apprentice, eager to learn and master the artistry.

Outside the office, my friends were struggling artists, waitresses and students, all of us transplants to this hub of hippie subculture. The city was dotted with rock ’n’ roll landmarks like Haight-Ashbury, the black Jefferson Airplane mansion or the locus of the infamous Summer of Love, Golden Gate Park. The music culture was dominant and even with my peon job, I carried a certain je ne sais quoi by association.

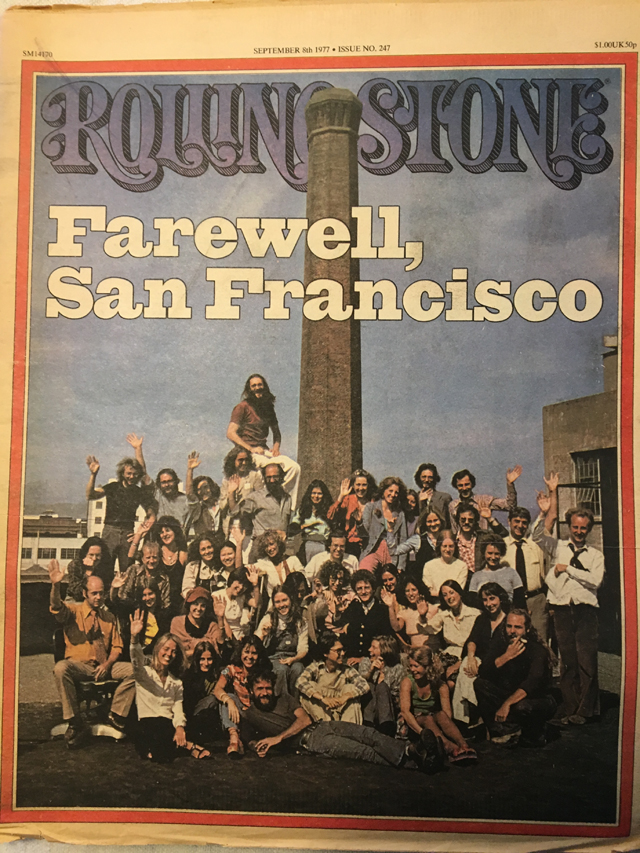

The magazines founder and owner, Jann Wenner, a Steve Jobs wunderkind type, eventually decided that his ambitions were bigger than the funky warehouse South of Market and he moved the entire operation to New York City. The new offices, in a beautiful art deco skyscaper at Fifth and 57th, were slick, spotless and camera-ready for the advertising execs who were making Jann a very rich man. I had chosen to stay behind in San Francisco to work on Jann’s new magazine, Outside. Still, I could not shake my connection to the mothership and often came to New York, to hang out in the office and socialize with my friends. It was a like a club that granted lifetime membership. From high school reunions to future job interviews, that membership was a notable perk in my life for years.

In 2007, I attended a reunion in San Francisco marking the 30 years since the magazine moved east and changed its DNA. I was now an art director at a New York newspaper, divorced and a mother of two teenage girls. Although I had stopped keeping up with the magazine, I realized that its impact on me was unmistakable. As I greeted old co-workers, some in academia, some in the digital world, and a few still living the dream in San Francisco, I was struck by how these people and that time had left their fingerprints all over me. That heady time (no pun) had not only given me an amazing soundtrack for my memories but also a belief that my opinion mattered, that individual voices could and should speak up to institutions of power.

And the music? I am now the proud owner of a vintage Dual turntable with a record collection that grows with $1 yard sale finds. Listening to Bob or Mick or Aretha on vinyl, the thrill is definitely not gone.

The author, of Southold, is retired from a career in magazine publishing. She was creative director at Women’s Wear Daily and a longtime art director for the New York Observer.