$1M fish passage project at Woodhull Dam to provide boost for local marine ecosystem

Beginning each year in late February, Byron Young, a retired fisheries biologist for the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, would head down to Woodhull Dam in Riverside. For two or three days a week starting around 2010, he led an effort to catch thousands of river herring and American eel during the run season and physically move them across the dam.

It was a laborious process of either dip netting or cast netting to catch the fish and eels and then carrying them over the dam and upstream by bucket brigade. For Mr. Young, it was an enjoyable experience and a rewarding one. He would often bring his young grandson, who loved to help.

“My only rule with him was don’t fall in,” Mr. Young recalled. “He was going to get wet, but just don’t fall in.”

A couple of hours of work would yield several hundred fish making their way over the dam, allowing them to continue upstream toward their natural spawning area.

All that manual labor will soon be a thing of the past.

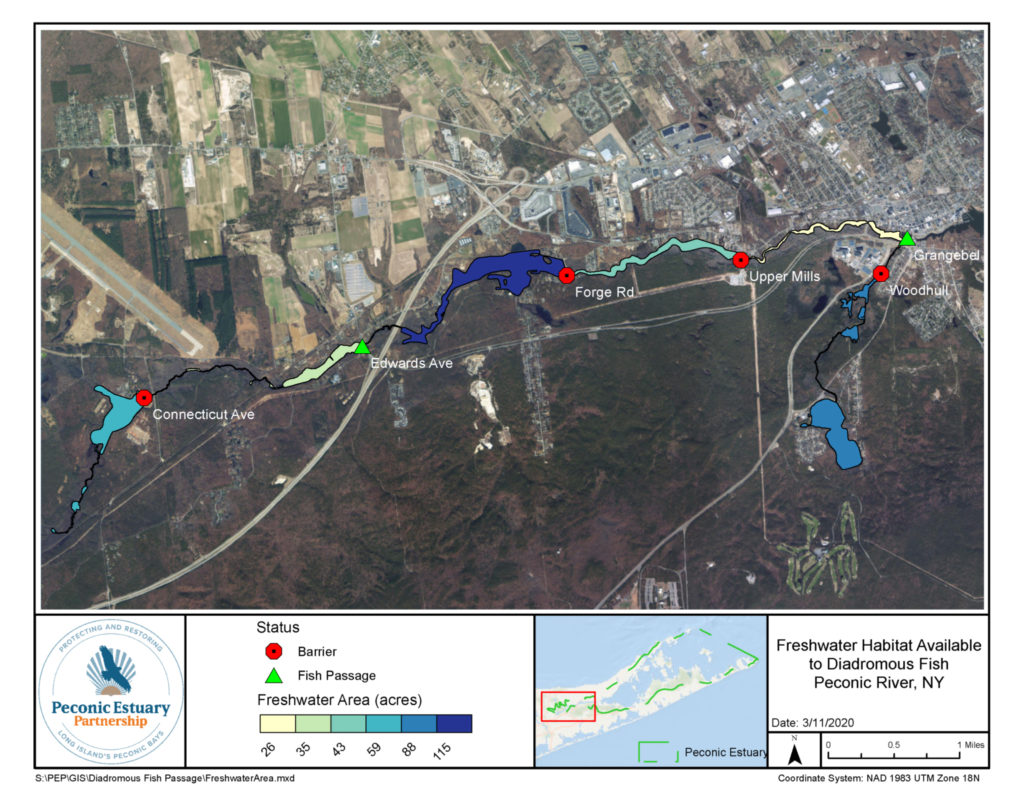

Construction began at the end of December on a nearly $1 million fish passage project that is expected to restore “critical spawning and maturation habitat for river herring and American eel” and provide a major boost to the local marine ecosystem. The project is a partnership with the DEC, Peconic Estuary Partnership, Southampton Town and Suffolk County.

“[The] Woodhull Dam fish ladder is the culmination of a real long period of time working to get this done,” Mr. Young said.

The dam is located on Little River across from the Suffolk County Center. Little River is a tributary of Peconic River and runs down to Wildwood Lake, where about 95 acres of spawning habitat will be opened from the fish passage. The dam had been built in the late 1800s for a cranberry farm that once existed in the area, Mr. Young said. The area is now home to a 165-acre preserve known as Cranberry Bog Nature Preserve.

“These fish have been prevented from getting there on their own for over a century,” said Mr. Young, who lives in Ridge. “Once this project is done and fish can pass on their own, we should see increased reproductive success in the Peconic River.”

Joyce Novak, the executive director of Peconic Estuary Partnership, said the project has been in the works for several years. The Peconic Estuary Partnership worked with partners at the state and county levels to secure funding for the fish passage. Ms. Novak said about $500,000 of the final price tag came from the county.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is leading construction of the fish passage, which is expected to be completed by the end of March.

The river herring form the base of the food chain, Ms. Novak said, and are important for fish like striped bass that are in larger bodies of water.

“You really need to preserve that base of your food chain to allow everything above it to thrive and be successful,” she said in explaining the importance of the project. “We’re seeing this around New York State, sort of this need for either dam removal where that’s possible or these fish passages to allow things like eel and smaller fish to get to their historic spawning grounds.”

Mr. Young said reconnecting streams either through dam removal or fish passages benefits not only freshwater fish that eat the eggs or young, but mammals such a raccoons and river otters and birds like osprey, eagles and herons.

“When they get into the ocean, there’s a whole other suite of animals and fish that eat on them — seals, striped bass, bluefish, probably a fluke on the small ones,” he said.

In this instance, removal of the dam wasn’t feasible as it likely would have disturbed the natural wetland and park area at the preserve. Ms. Novak said dam removal is often complicated.

She said it was a long process with multiple stakeholders at the table to determine not only whether to proceed with a fish passage, but the specific type of passage to best serve the area.

The design of the fish passage, according to the DEC, is a series of weirs or “steps” and resting pools to help the fish climb upstream. A separate eel passage will be mounted alongside the fish passage and the structures will bypass the current culvert and be constructed through the existing dam. A video monitoring system will also be installed near the exit of the fish passage. Mr. Young said he expects once the fish passage is up and running that people will be able to visit and watch fish go through the ladder.

“It’ll be educational,” he said, noting how in an area of Maine, an annual run on Damariscotta River has turned into festival known as the Alewife Festival that brings people together to support the upkeep of the fish ladder. Photographers capture images of bald eagles and osprey catching alewives.

The Woodhull Dam project is part of a larger effort to restore 300 acres of fish habitat on the entire Peconic River system, Ms. Novak said. In 2016, a fish passage project was completed at the Edwards Avenue Dam and in 2010, a fishway was built at the Grangebel Dam. The Peconic Estuary Partnership will be seeking funding for the next fish passage at Upper Mills Dam, which will open 40 acres of spawning. Upper Mills Dam is located west of Woodhull on the Peconic River near Snowflake Ice Cream Shoppe.

“It’s so exciting to watch something that so many people have worked so long to make happen and come to fruition,” Ms. Novak said. “It really is amazing.”