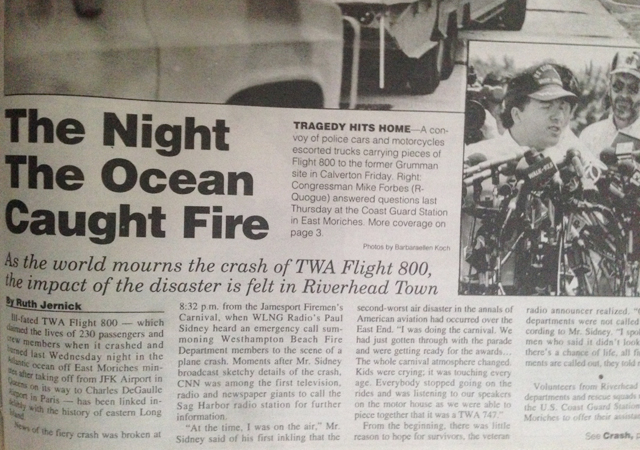

Twenty years later, remembering TWA Flight 800

A large flash of light filled the night sky south of East Moriches just after 8:30 p.m. on July 17, 1996.

In seconds, 212 passengers and 18 crew members aboard TWA Flight 800, an international flight from John F. Kennedy airport bound for Paris, were killed as the plane exploded and crashed into the Atlantic Ocean.

The crash remains the third-deadliest aviation accident in U.S. history. Years of investigations by federal authorities found the explosion had probably been caused by the plane’s fuel tank, though many doubt the official explanation, clinging instead to an alternate theory that the aircraft might have been shot down.

Memories of the crash and its tragic aftermath remain vivid for North Fork residents who remember seeing the plane go down, rushing to the scene of the explosion and helping to recover pieces of the doomed aircraft as the fuel-slicked ocean burned.

‘I thought it was a meteor’

No more than 12 miles away from the explosion, Air National Guard engineer Mike Spindler of Calverton had just finished reviewing a checklist aboard a C-130 aircraft when he looked up and watched as a ball of flames fell toward the ocean, trailing a column of smoke.

The explosion seemed close to the aircraft, which was in the middle of a training mission.

“I thought it was a meteor or some kind of cosmic debris,” Mr. Spindler said in a recent interview.

Mr. Spindler, who has since retired from the military and now helps run Peconic River Herb Farm in Calverton, said those on board soon realized the explosion had been an aircraft.

Mr. Spindler’s C-130 flew toward the location of the explosion, but was forced to circle the burning wreckage due to falling debris. All through the night, Mr. Spindler and his fellow guardsmen dropped high-illumination flares around the site to help the recovery efforts below.

Mr. Spindler said he recalls seeing sheets of metal and white painted parts of the aircraft adorned in red stripes. The water, he said, was on fire.

During his time in the service, Mr. Spindler had worked on other recovery efforts, like securing fighter plane crashes in upstate New York. But the crash of TWA Flight 800 contained more destruction than he had ever seen.

“One minute you’re flying along to Europe to visit your family and the next …” His voice trailed off.

“It was a terrible tragedy,” he continued. “You’re looking down there thinking ‘God, there was people down there.’ ”

Racing to the scene

As the 110-foot-long vessel raced away from Plum Island toward the site of the TWA Flight 800 crash, first responder Christopher Schmidt of Stony Brook, then a 23-year-old safety technician at Plum Island, was prepared to save lives.

He and the other employees on the boat — captains David Henry and Steve Redman, deckhands Woody Browne and Lou Meditz and fellow first responders Mike Norklun and Joe Loretz — had scrambled to the boat after hearing reports of the crash over the emergency service’s radio.

“If we could have made that boat go 100 mph we would have,” Mr. Schmidt recalled 20 years later. “We were all standing on the deck, champing at the bit ready to help some people.”

But as they approached the scene of the crash in the fading light, Mr. Schmidt said he began to understand a painful truth: They wouldn’t be pulling any survivors out of the water that night.

“It was catastrophic, and then we knew,” he said. “We weren’t prepared for what we went into.”

Mr. Loretz, also of Stony Brook, said the Plum Island boat was the first major vessel to arrive on the scene.

“There was a lot of kid’s toys in the water,” he said. “It was somber. You could hear a pin drop.”

The ship weaved between flares and smaller Coast Guard cutters; the men used grappling hooks to pull pieces of the ship aboard or tow them to nearby recovery vessels. All the while, choking fumes from the burning fuel burned their eyes and throats.

“The jet fuel was so acrid, everybody’s eyes were burning for days,” Mr. Loretz said.

The men pulled debris from the water throughout the night: chunks of Styrofoam, sheets of metal and a sack of mail that had been destined for Paris.

They saw bodies too, but didn’t have the tools to pull them aboard, he said. As the sun rose the next morning, Mr. Schmidt said they realized the scale of the destruction. The vessel returned to Plum Island after working the crash site for more than 12 hours.

The trip home was silent, Mr. Schmidt said. He didn’t fully grasp what he had seen, even after returning home to Stony Brook. Then he saw a television news report showing families of the victims being led away to speak with investigators.

“I suddenly [connected] human beings to those letters that we saw,” he said. “The suitcases, clothes. That was really, really difficult … I think about it a lot. Every time I get on a plane.”

“Even today it affects you,” Mr. Loretz added. “Even today, 20 years later, it seems like just yesterday. You learn to appreciate every day.”

Local reporter among first to see catastrophe

Steve Wick of Cutchogue was a general assignment reporter for Newsday when TWA Flight 800 went down and was the first reporter at the scene just hours after the crash.

Mr. Wick — who rode to the crash site with Newsday photographer J. Conrad Williams Jr. on a Hampton Bays lobsterman’s boat — said he was struck by the mirror-like stillness of the ocean at the time.

“It was almost like the bay, when you see the Peconic as calm as it can get,” he said. “It was odd to be thinking that on such a beautiful summer night … that something absolutely horrific had happened.”

As they made their way into the ocean, Mr. Wick said the two men could hear other boat captains over the radio, reporting debris and bodies everywhere. He remembers one captain said there were body parts in the water; the captain needed a bigger net to fish them out.

The thick black smoke from burning jet fuel blotted out light, so only the spotlights of nearby ships were visible. The water, he said, was covered with debris: “Luggage, backpacks, shoes, cushions, parts of the plane itself, insulation and the wiring, just scattered everywhere,” he said. “You just start to realize that this is an absolute catastrophe.”

Reflecting on the crash’s anniversary, Mr. Wick noted that he and his photographer were simply witnesses to the tragedy.

“At no point does it compare to a family that lost everything,” he said. “We were just observers.”

Mr. Wick said all reporters have stories that “stick with you,” and TWA Flight 800 was “one of those that seemed impossible to accept.” Long Islanders were also reshaped by it, he said.

“The overwhelming sense of safety in flying, for many people, was absolutely shattered,” he said. “It almost made no sense that so many people lost their lives to something that doesn’t seem to add up, but it was just an accident.”

Mr. Wick and Mr. Williams retold their stories this week in a Newsday video marking the anniversary.

Plane pieces — and victims — at the command post

Jamesport Fire Department chief John Andrejack, who was a member of the sheriff’s department’s marine unit at the time of the crash, said TWA Flight 800 was the first time he had to cover a “mass casualty” situation. By the time Mr. Andrejack arrived at the command post at a nearby coast guard station, pieces of the airliner were being delivered.

The plane parts and other debris were strewn on the lawn of the Coast Guard station.

“I remember a lot of pieces of aircraft coming in. Seats, luggage,” Mr. Andrejack said. He also remembers the temporary morgue set up in a garage, where victims’ bodies were laid. In the weeks that followed, members of the sheriff’s department would scour the beach on all-terrain vehicles, looking for parts from TWA Flight 800 — or victims’ remains — that washed ashore.

The amount of carnage Mr. Andrejack saw made an indelible impression on him.

“Nothing compared to that, except for Ground Zero,” he said. “The wildfires, other bad accidents I’ve been at, nothing compared to that.”

Mr. Andrejack said the mood was “very somber” as first responders worked the area and agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigations took over the inquiry into the crash. The pieces collected at the Coast Guard station would later be moved to the former Grumann facility in Calverton, where investigators would piece together as much of the plane as possible.

Weeks, and even years later, speculation continued over whether the tragedy was an accident or an act of aggression.

Mr. Andrejack remembers one private pilot who came to the station, convinced he saw a streak of light approach the plane just before it exploded. That man’s testimony was recorded by investigators, who ultimately determined the crash was caused by an explosion in the plane’s fuel tank.

“I really don’t know,” Mr. Andrejack said. “I will always remember it, that’s for sure.”

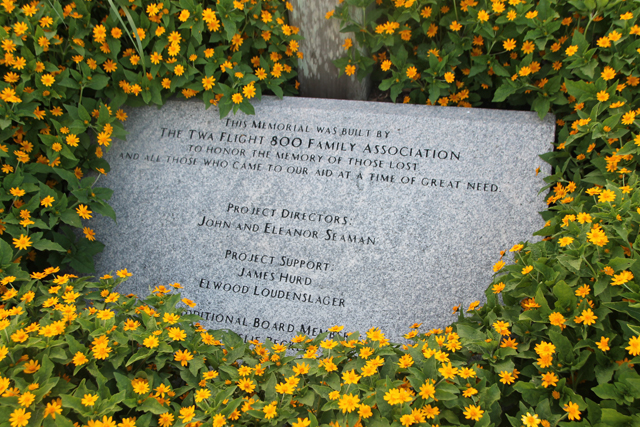

Top photo caption: The TWA Flight 800 memorial at Smith Point County Park. (Credit: Grant Parpan)