When the Spanish flu struck in 1918 and its impact here

The fetid stench of death hung in the air.

It was 1918, and one of the greatest killers mankind has known was busy doing its dirty work on the World War I battlefields of Europe. This effective killer was unseen, mysterious in its ways. It knew no boundaries, wore no uniform and held no allegiance. This merciless killer just attacked — quickly and brutally.

The 1918 Spanish influenza was a killer, the likes of which the modern world had not seen before. Estimates are that the flu infected 500 million people (about one-third of the world’s population at the time) and killed between 50 million and 100 million people from 1918-20. Among them were 675,000 Americans.

Staggering statistics.

“They ran out of coffins. They were stacking them up like cords of wood.”

Southold Town Historian Amy Folk

This devastating global disaster was said to be responsible for more deaths than World War I, World War II and the wars in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan combined, with more people dying in a single year than the four years of Black Death bubonic plague from 1347-51.

Because of the war and the flu, there was a shortage of coffins. Burying the dead became a terrible ordeal.

“They ran out of coffins,” Southold Town historian Amy Folk said. “They were stacking them up like cords of wood.”

The sheer number of bodies was such that some people dug graves for their own family members.

“The mass mortality led to macabre scenes,” read an account on history.com. “Red Cross nurses in Baltimore reported instances of visiting flu-ravaged homes to discover sick patients in bed beside dead bodies. In other cases, corpses were covered in ice and shoved into bedroom corners where they festered for days.”

The first mention of the term Spanish Influenza in a Long Island newspaper, according to a search of the NYS Historic Newspapers digital archive, came in the South Side Signal of Babylon on July 19, 1918, when the paper reported in its world news section that 80% of the Spanish population had been infected. Two months later, the same paper would report that an area doctor who had been serving in the war had been diagnosed with the illness.

By September 1918, flu was added to the list of reportable diseases in New York City, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The earliest news account of a North Fork resident being diagnosed with Spanish Influenza came in the Sept. 20, 1918, issue of the County Review, an earlier version of the Riverhead News-Review, according to the same archive. Milton Hallock of Riverhead had been serving in the Navy when he was diagnosed. He was treated at a Navy hospital in New London, Conn., where his parents were said to have visited him.

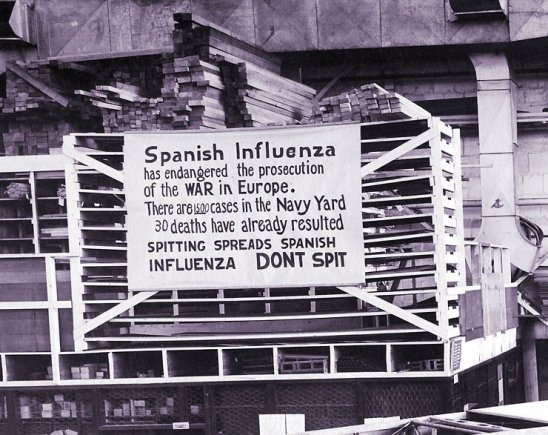

The following week the County Review published guidelines from the federal government: “Keep out of crowds and away from theatres, movie houses and other places where people come together in large numbers. If you have a cold, start treating it immediately; carry a clean pocket handkerchief and when using it do not flap it about. Keep the nostrils and other breathing passages clean. Three times a day use a gargle made up of half a teaspoonful of table salt, half a teaspoonful of baking soda and six ounces water.”

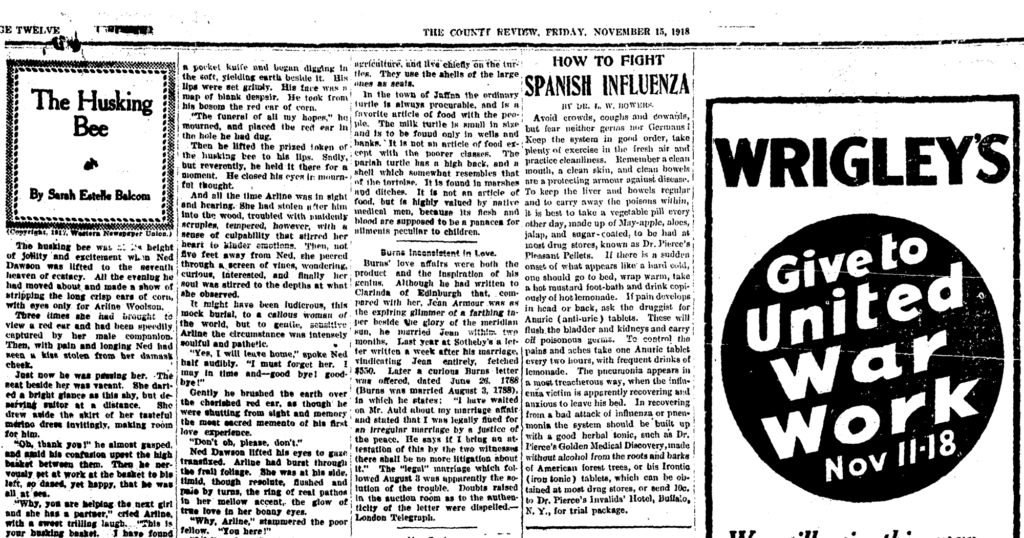

In November of that year, the County Review published a column from a doctor giving advice to soldiers titled “How to Fight Spanish Influenza.”

“Avoid crowds, coughs and cowards, but fear neither germs nor Germans,” the column began.

In January 1919, 706 cases and 67 deaths were reported in New York City, according to the CDC.

Ms. Folk said the effect of the Spanish flu was felt in Southold in the 1920s. A letter written by Roy Latham of Orient, in possession of the Oysterponds Historical Society, indicates that.

“The flu hit Orient so hard,” he wrote in the letter, dated Feb. 8, 1920. “Willis Latham died on Thur. night and Bert Terry and Vernon Latham both died today. Agnes is so sick she can’t raise her head from the pillow. Rufus Tuthill almost died the other night, but is now better and there are nearly a hundred other cases in Orient. Bert, Willis and Vernon all took the pneumonia and several others had it, or have it … This is the most terrible time Orient ever [knew].”

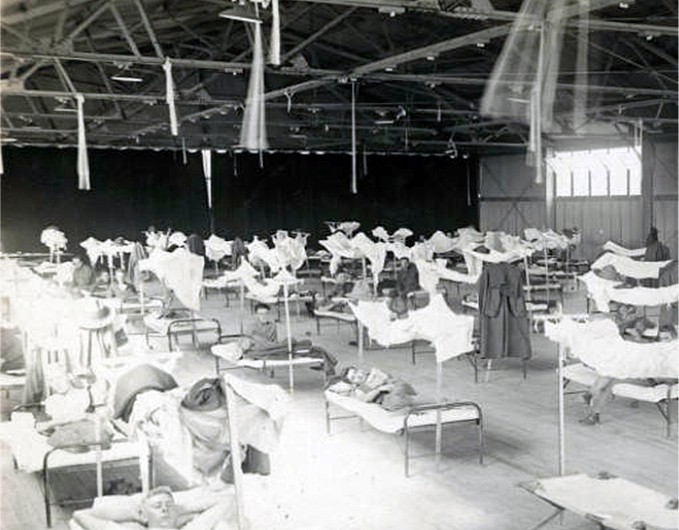

The influenza came in three waves. The first wave petered out with the arrival of summer in 1918. But the mutating virus roared back in the fall. Doughboys returning home undoubtedly spread it further on American soil. In September, the virus struck Camp Devens in Massachusetts. The camp was quarantined, but not before troops were moved from there to Camp Upton in Yaphank on land now occupied by Brookhaven National Laboratory, according to Eric Durr’s article for Army.mil. By the time the epidemic was considered over at Camp Upton, 6,131 soldiers had been hospitalized and 404 had died, Mr. Durr wrote.

One theory is that people with robust immune systems had those immune systems overreact, effectively turning against their own bodies. Mr. Durr outlined this possibility in his article when he described the case of one soldier, Pvt. James Down, who entered the Camp Upton hospital and died Sept. 26: “An Army pathologist clipped a piece of Down’s lung, preserved it in wax, and sent it to the Army Medical Museum. In 1999, that section of lung helped doctors at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology determine what made the 1918 virus so deadly. Researchers in 2007 theorized that the 1918 flu forced victims’ over-stimulated immune system to kill the patient as it tried to fight off the virus.”

The 1918 pandemic was said to have lowered life expectancy in the United States by more than 12 years. Although major cities were hit hard, the disease didn’t discriminate. “There were reports from Eskimo villages in Alaska and jungle villages in the middle of Africa of 100% mortality,” John Barry, author of “The Great Influenza,” said in a presentation to the Virginia Historical Society.

It seemed no place was safe. With no vaccine and no antibiotics to battle it, the influenza tore society at the seams.

“It was an astonishing, devastating epidemic,” Gina Kolata, a science reporter for The New York Times and author of “Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus That Caused It,” said on a C-SPAN program.

So, where did this all begin?

The origin of the influenza is a question that may never be answered to complete satisfaction. Some think an Army camp in Kansas, Camp Funston, was ground zero.

Whatever its origin, the H1N1 avian-borne virus spread within months with the aid of World War I troop movements. American soldiers carried it over with them to Europe. Some soldiers died on loaded troopships and were buried at sea.

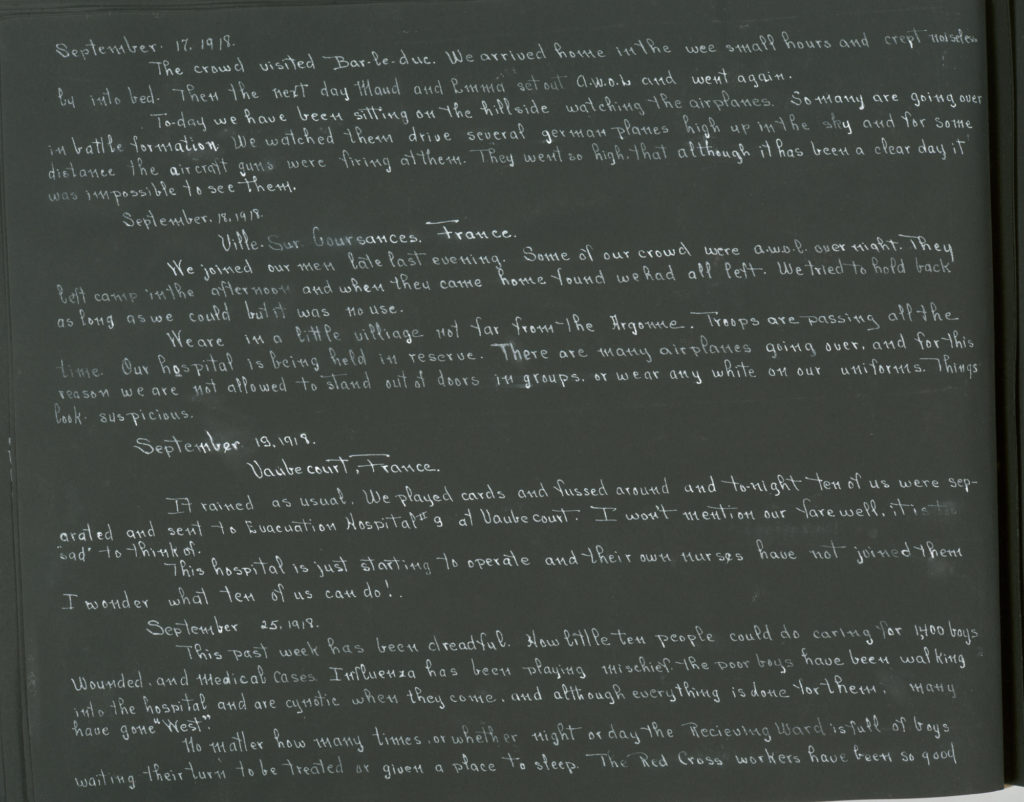

The filthy battlefield trenches proved to be a perfect breeding ground for the flu. An estimated 43,000 American servicemen died, including Irving E. Smith of Sayville, reported to have died from the virus in October 1918, while serving in Tours, France in one of the earliest accounts of a fatality from Suffolk County. It would be four years before his body would be returned to the United States.

The symptoms associated with the influenza were horrifying. People bled from their nose, mouth, eyes and ears. They turned blue because their blood wasn’t getting enough oxygen, their lungs filled with fluid and they suffocated.

What was particularly unnerving about the 1918 virus was how it took down strong, healthy people. Mortality was high in the 20-40-year-old age group, as well as those under 5 and older than 65, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“It struck down people who were in the prime of their lives,” said Sarah Grunder, a Suffolk County Community College associate professor of history.

Just how rapidly people’s conditions deteriorated was unsettling as well. Stories were told of people dying within hours of developing the flu.

The Spanish flu was misnamed because it surely wasn’t confined to Spain. What Spain had — because it was neutral throughout the war — was a press that was relatively free from wartime censorship to report about the influenza. The American press, meanwhile, was muzzled by the Sedition Act while the government played down the threat posed by the influenza.

Even so, Mr. Barry said, “People knew that this was not ordinary influenza by another name.”

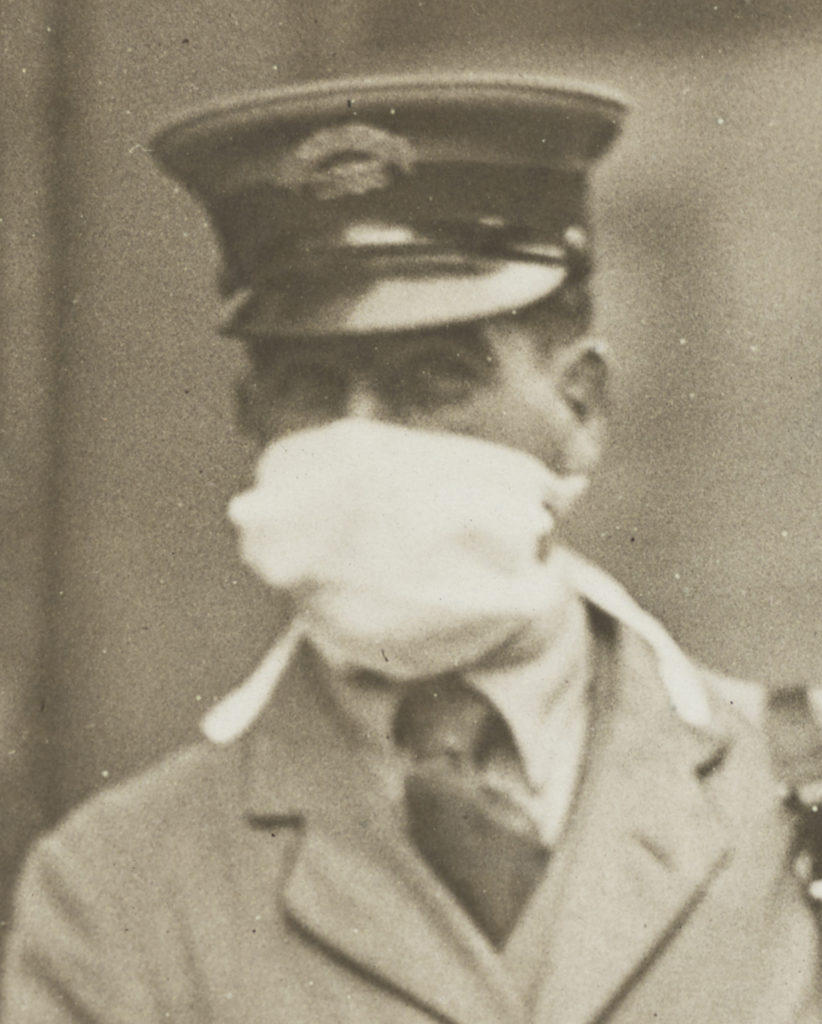

Control efforts were limited to isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants and limitations on public gatherings, which were applied unevenly, according to the CDC.

“It was handled differently by different cities, by different states,” Prof. Grunder said. “Philadelphia handled it very poorly. New York City fared a little bit better.”

Philadelphia ignored warnings and went through with a parade to raise money for war bonds in the fall of 1918, when the virus was said to be at its most virulent. The city then was hit with about 16,000 deaths and half a million cases of influenza, according to the Penn University Archives & Records Center.

A nightmare scenario unfolded. The invisible phantom terrified people. The black plague had not returned, as rumors suggested, but scenes that might have come from the plague-infested Middle Ages materialized.

Matters were further exacerbated by a shortage of health workers because of the war. Hospitals were overloaded with flu patients. Schools, private homes and other buildings were converted into makeshift hospitals. Families were wiped out.

“It’s like every family was playing Russian roulette when somebody got sick,” said Mr. Barry, who noted that some people starved because people were afraid to bring them food. “In 1918, society began to dissolve.”

New York City was better positioned than Philadelphia since it adapted measures from its earlier campaigns against tuberculosis. It instituted staggered business hours to avoid rush-hour crowding on the public transit system and set up more than 150 emergency health districts and centers to coordinate home care and case reporting, according to an article by Francesco Aimone about New York City’s public health response to the influenza. The article noted an amendment to the city’s sanitary code requiring all people “to protect their nose or mouth while coughing or sneezing.”

Interestingly, New York City schools were kept open during the crisis in the belief that students would be healthier in school than at home.

The influenza became such a part of Americans’ lives that children even incorporated it into a song: “I had a little bird. His name was Enza. I opened the window and in-flu-enza.”

Mr. Aimone wrote that New York City emerged from the pandemic having recorded approximately 30,000 deaths out of a population of roughly 5.6 million due to influenza or pneumonia. The city had an excess death rate per 1,000 of 4.7, lower than either Boston (6.5) or Philadelphia (7.3).

By sheer coincidence, the era of the 1918 Spanish flu came up in Prof. Grunder’s class in early March. The professor clearly understood her students were all living history in the making with the current coronavirus pandemic. She recalled, “I told them if they keep journals about it, the [future] historians of the 21st century will thank them.”

With reporting from Grant Parpan.