Thank you to our front line health care workers

This month, our colleagues at northforker profiled five hospital and nursing home staff members working in all facets of their facilities who played a role in the fight against COVID-19 this year.

On this holiday, we want to offer our gratitude to them and all their peers making a difference in so many lives.

Here are their stories.

The doctor who led Covid care at Eastern Long Island Hospital

Jarid Pachter | Medical director, Quannacut Outpatient Services

Dr. Pachter is an osteopath and primary care physician with offices in Southold and Riverhead. Last spring, he was working as a hospitalist at Stony Brook Eastern Long Island Hospital in Greenport — and as the area suddenly became one of Long Island’s first COVID hot spots, he was called on to lead the clinical task force taking care of COVID patients. “I came in on a Saturday in March because there was a patient who tested positive, and from that point on, I basically lived at the hospital,” he said. “It went quickly from this thing on the news to becoming your life.”

“The benefit of treating patients with coronavirus in our hospital is that, even though we’re part of a big healthcare system, we’re still ultimately a small community hospital. I recognized quite early on that the most important thing in treating these patients was having high-quality nursing care and close attention to their cases. I think we were ahead of the curve in recognizing that we don’t need to rush to put these people on ventilators, nor were we involved in any sort of big study using fancy experimental drugs that were unknown to work at the time.

Everybody of course now talks about the pandemic of 1918 — not much has changed since then. You use masking and social distancing, and even the medical care of these patients is basic bread-and-butter medicine, monitoring their vital signs, making sure their oxygenation is good and being patient with them and calming their anxiety and treating some of their other medical problems that go along with it. I don’t want to suggest that everybody’s going to get better with just close nursing, but I think as a small community hospital we were able to avoid having to put a lot of people on ventilators by being patient and having that continuity of me as the doctor, seeing these patients almost every day, and having the same nursing staff rather than changing shifts every couple of days. And I can’t praise the nurses enough for how they rose to this challenge.

Just as the nature of our job, we deal with mortality a lot and it’s always difficult. But the volume of patients who would come in and who were potentially dying and who actually did, and the anxiety and sadness of them being alone was different and more difficult. And hopefully not something we will ever have to deal with again.

There’s still this misconception that it’s being overblown.

Jarid Pachter

For every horrible situation there is clearly a silver lining, and that was the community support, the donations or even the blasting horns or pots banging at a certain hour of the day near where I live. As somebody with a growing family of my own, to explain to my kids that you’re part of that was really special. The camaraderie and seeing the team across the board rising to the occasion of something so challenging, it makes me very proud.

It’s extra insulting to me when I see people not wearing masks. Just like you do with a patient, you try to empathize and you realize that a lot of people who are still not doing what they should be doing probably have not had any contact with anybody who has gotten coronavirus. There’s still this misconception that it’s being overblown. But if people gave healthcare workers the donations and the food and the applause and the pots and pans, the best gift that anybody can give us and themselves is to keep wearing a mask and keeping social distance, especially when the weather turns cold and people start congregating indoors. Otherwise all the thank you’s are meaningless, because actions speak louder than words.”

The Peconic Bay Medical Center worker who became a Covid patient

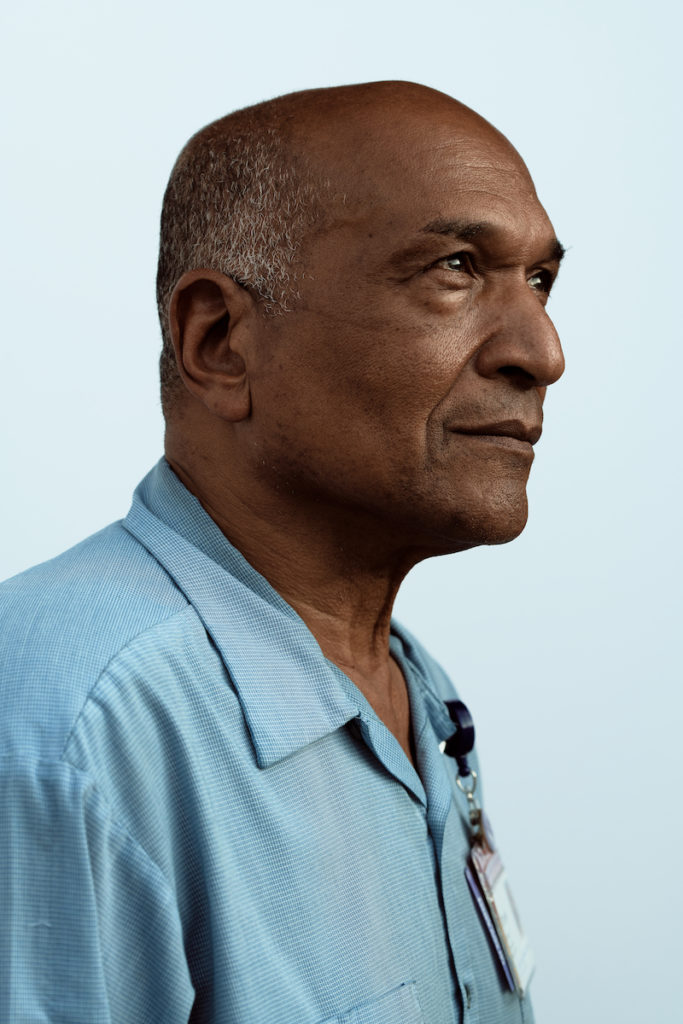

Charlie Parker | Environmental services, Peconic Bay Medical Center

Some of the roads were still dirt when Charlie Parker was growing up in Riverhead, where his dad worked as the head of housekeeping at what was then called Central Suffolk Hospital and is now Peconic Bay Medical Center. A former musician and military veteran, he traveled to Saudi Arabia, Africa and Ireland in a 39-year career in the Air National Guard before returning full circle to work in environmental services at the hospital.

“I work at the hospital from 4 a.m. to 2 p.m. One day in early March, I was walking across the street to the front door of the lobby and I was short of breath. I thought, what is this? I’m a very active guy; I had just done nine miles walking around the track. But I had suffered in the past with sarcoidosis, which is an autoimmune deficiency lung disease, and I’m a survivor of prostate cancer.

So I took a test — you know, the brain tickler, not good. On the sixth day of waiting for the results I told my wife, ‘I can’t take it. I can’t breathe.’ I couldn’t walk from the living room to the bathroom. She took me to the emergency room and the last thing I remember is the security guard asking me if I had traveled outside the country and then I collapsed into a wheelchair.

I had double pneumonia and was positive for COVID. Everyone asks me how I got it, but I have no idea.

I was in the hospital for five and a half weeks — no visitors. My wife and kids could call, but they didn’t because just talking would bring on the hacking. Everyone in the ICU, they were fantastic. I remember them saying, ‘We got you, Charlie. You can do this, child. We love you.’ Mr. Mitchell [Andrew Mitchell, the hospital’s CEO], would come to the nurses’ station and check on me all the time. They really pulled me out of this whole thing.

It’s just like in the military. We go into the battle.

Charlie Parker

The housekeepers would come into my room to clean and they’d have two masks on, and a plastic overgarment, and the sweat was just dripping off. But they worked as hard as they normally do. It’s just like in the military. We go into the battle. And that’s the thing you got to admire. They’re going into danger, knowingly. Everybody else is leaving and they’re going in. Same thing with nursing. It was like a war zone, but nobody quit their jobs. You have some strong, tough people and caring professionals.

I didn’t know until I had left the hospital and come back to work that I was this far from the ventilator. So I was blessed, lucky, whatever you want to call it. It just wasn’t my time to go. I do still have some shortness of breath, but I’m better than what I was, believe me.

I want to tell everyone to be safe. This is serious and it’s not going anywhere. The mask right now is the vaccine. And I’d definitely say thank you to the staff and the community for their support. Not only for helping me, but helping the hospital through a hard time. They all know at the hospital the possibility that it could come back — people are still doing foolish things, and even one person can spread it so easily. If it does, they’re ready for it.”

The director of nursing at San Simeon by the Sound

Kelly Moteiro | Director of nursing, San Simeon by the Sound

Growing up in Farmingville, Kelly Moteiro always wanted to be a nurse. And by age 18 she was working in a nursing home. “I went to work in a hospital for a little while, but I missed long-term care — hearing the stories of the lives that they lived and being able to make a difference,” she said at her office at San Simeon by the Sound in Greenport, where she’s been director of nursing for the past four years.

“This is like nothing any of us ever dreamed. We shut down visitation on March 10, before it was mandated. I came out here and stayed in the motel across the street for two and a half months without going home at all. Now I go home on the weekends and maybe a night or two during the week, but I still stay out here across the street. I have a 19-year-old daughter in college and my husband is at home, but they know my job. I felt like I can’t ask my staff to go the extra mile unless I live it with them.

The residents, too, are isolated. We have visiting again, but it’s by appointment and it’s different. And it’s already over six months of living this. That’s just crazy. But we have been blessed and lucky here. It’s hard work — plus definite luck — that we have never in the whole time had any resident with COVID.

We were on the national news. My brother was like, ‘You’re the only good news in this whole situation.’ At the same time, I felt bad: The directors of nursing at these other facilities are some of my closest friends and my heart breaks for what they went through. They had freezer trucks in their parking lot because they couldn’t even store all the bodies. they’ll never be the same.

We’re a nonprofit. So when the governor mandated that nursing homes take COVID patients, I didn’t have ownership telling me, ‘You have to, because they tripled the Medicare rate.’ Some people see an executive order from a governor and think, Oh, I have to do it. But I guess I’m different.

I do believe it was in nursing homes already, brought in by the staff, but that order didn’t help. I had a lot of fights with case managers at the hospitals, but I said, ‘I have nowhere to put these patients and I don’t have the staff to take care of them. So I’m not infecting my healthy facility. Tell the governor to come out here himself to my front door.’ I’m stubborn in that way.

The people here are my family and I refuse to infect this place.

Kelly Moterio

The amount of support we got was insane: messages, cards, food, gifts for the staff. Claudio’s restaurant sent their DJ on Memorial Day, and it was the first time that the residents were really outside and they just loved it. It’s such a tight community and the support was beautiful to see — and it was appreciated by everybody, staff and residents.

I’m truly lucky with such amazing staff that they understand what we’ve accomplished and understand that our efforts are not just for a gold star. It’s because people are alive. Even though I didn’t live the devastation others did, it definitely changed me as a person. I don’t think I’ve ever prayed so much and looked at life just very differently. I think Mother’s Day was when it hit me the most. I was looking around at all the ladies and I thought, they’re here. And so many other places, you can’t say that.”

The chief nursing officer at Stony Brook Southampton

Althea Mills | Chief nursing officer and vice president of patient services, Stony Brook Southampton Hospital

Althea Mills grew up in Tobago (“an island smaller than Long Island”) before emigrating with her family to Brooklyn and relocating to raise her family in Brentwood. Starting as a nurse’s aide, she has worked her way through the ranks of nursing and two years ago was elevated to her leadership role at Stony Brook Southampton Hospital. “I am very spiritual, and I do what I do because I feel that God has a mission for me to accomplish,” she said. “So I was prepared for this, even though I wasn’t consciously doing that.”

“In early March, we had the first COVID-19 positive patient in Suffolk County. That Saturday morning life as we knew it changed.

We were fearful and anxious, not just about contracting the disease, but the governor’s mandate to prepare for a surge was a heavy lift. Not only did we have to come up with beds, but also we had to staff and service those additional areas. About five days into the crisis, we gelled. We began to feel a lot calmer and operate like a well-oiled machine. I will always remember the look on the faces of each other when we realized, ‘We’ve got this.’ We knew for us to make it through this crisis, we could only fight one war, and that was COVID-19. We didn’t have time to be fighting each other.

In nursing administration, I’m typically working on a computer, collaborating with middle management and leaders to pass on strategic goals. During COVID, forget it. I knew I had to get out and be on the front line myself. I had to change into scrubs and sneakers. I was converting office space into hospital wards, starting IVs. I needed to let my staff see that I was leading by example and I was not fearful of what was coming. And to support them and hold their hands and give them the strength to carry on.

It’s an opportunity and a privilege to be of service to others.

— Althea Mills

One Saturday morning, I was waiting for a package. A couple of cables were missing from a monitor that we needed in order to expand the ICU. But when the FedEx package arrived, there was nothing looking like cables inside. I jumped out of my bed, I left my home in Brentwood, went to Eastern Long Island Hospital in Greenport to get the cables we needed, and then drove from Greenport to Southampton. When I had delivered the cables, I looked down and realized, “I’m still in my pajamas!” That memory will always stick out to me — when I knew that I could meet my patients’ needs and I wasn’t letting down my staff that was depending on me. That was one of the best days through this crisis.

This Thanksgiving I am very grateful for life. I have close friends who spent weeks in the hospital, and some who died. I myself have an autoimmune condition that puts me at high risk. I’m grateful for the tremendous outpouring of love and support we received from our community. And I am forever grateful for the leadership of this hospital, and my coworkers who are an extended family that I have grown to love and treasure.

I am grateful that God gave me the opportunity to be helpful, to impact people’s lives when they are at their most vulnerable. Anybody who chooses to work in that sacred space between sickness and death should count themselves blessed. It’s an opportunity and a privilege to be of service to others.”

The director of nursing services at Peconic Landing

Mary Lavery | Director of nursing services, Peconic Landing

Mary Lavery grew up in Rocky Point, where helping her grandmother care for her grandfather as a teen sparked an interest in nursing-home work. Nearly three years ago she joined Peconic Landing, a retirement community in Greenport with more than 400 residents living in both independent and assisted-living facilities. In March, Suffolk County’s first-known COVID patient took a cab to the hospital; the driver also happened to work part time in the dietary department at Peconic Landing. Experts suspect this single exposure set off a cluster of deadly infections in the community.

“Around December, we started to hear about the outbreak overseas. Greg Garrett, our administrator, and I started ordering equipment really early on, which was great because we were prepared when it did hit us in, and rather hard. It was one sick person after the other, after the other, every day. We were isolating them and using all the PPE to take care of them and do whatever we could.

In the very beginning, staff members would go into a local restaurant with their badge on and oftentimes people would just back away. And that was very hard for them. They were amazing, the loyalty to the members and their love for them that they wanted so much for them to be well and recover.

Some of my staff are 18, 19 years old. They were working doubles for six weeks straight. Staff members were getting sick. And some were scared. How do you tell someone to come into work when they have young children or elderly grandparents that they live with? They were really good with each other and for each other. And we saved a lot of people.

Families have expressed that, ‘I haven’t held my mother since March.’ And I know. I have a mother who’s 82 years old and I know it’s been hard for everybody. We couldn’t have the dining room, which is very important to members for socialization. We couldn’t have group recreation activities and even simple things like a haircut or a manicure. We have a couple that’s been married for 65 years. He lives independently and used to come to the health center every day to sit with his wife and every night to have dinner with her. And now it’s only FaceTime. That’s heartbreaking. We’re trying to maintain any type of normalcy that we can, even just sitting down with somebody one-on-one to have a conversation about the song on the stereo or their family.

People who enter health care do it for a reason.

Mary Lavery

A lot of nursing homes did not report as well or as quickly as we did. And I think the community now acknowledges how we went about things, and that we turned it around as quickly as we did. I think not hiding things also probably got us help as far as equipment and testing. The overnight nurse sent me a picture at midnight one night, saying ‘Have no fear, Homeland Security was here!’ It was her posing in front of a whole room filled with gowns and gloves.

I would listen to the radio on the way home from work and people would say, “Something good came out of this. I cleaned out my closet and painted my bedroom.” And I’m thinking, I haven’t had a day off in 40 days. But people who enter health care do it for a reason. This is what we’re trained for, even though you hope it never happens. You just have to get up every day and say, ‘OK, I’m going back in.’ “