What happens to unidentified remains after case goes cold?

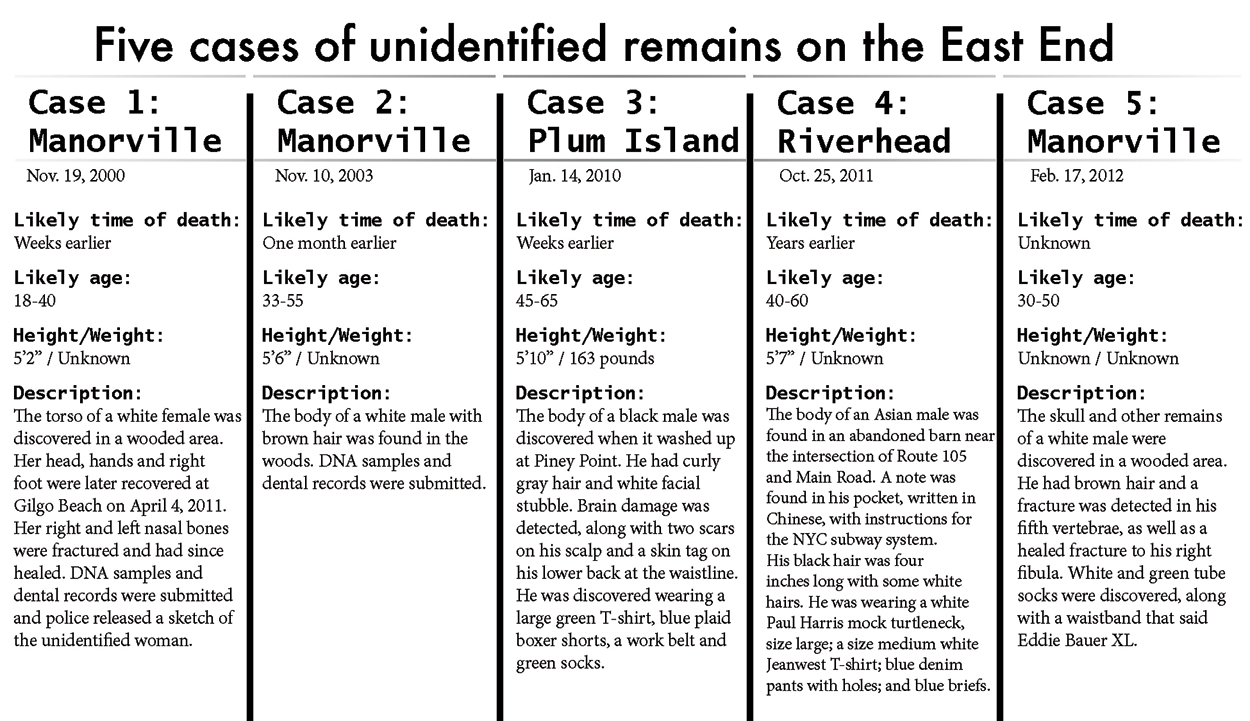

In February 2012, a Manorville man walking his dog in a wooded area near his house made a startling discovery: a human skull and other skeletal remains.

Five years later, all forensic analysts have discovered is that the remains were those of a man, likely white with brown hair and anywhere from 30 to 50 years old. His right fibula had been fractured but had healed.

The man’s fate isn’t unique. Since 1969, nearly 1,300 sets of unidentified remains have been discovered in New York State, according to the National Institute of Justice’s National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. Of these, 27 were found in Suffolk County, including three in Manorville, one in Riverhead and one on Plum Island.

Although many sets ultimately remain unidentified, experts nonetheless work continuously to find a match.

Identifying remains rarely entails a “bingo” moment, said Todd Matthews, director of case management and communications at NamUs. Instead, the process typically consists of building blocks that gradually connect and lead to solving a mystery.

The NamUs database was launched in 2006 in an effort to solve missing persons and unidentified decedent cases. The organization estimates that 40,000 sets of unidentified human remains exist nationwide; some are stored in the offices of medical examiners and coroners, while others were buried or cremated before they could be investigated.

The database comprises three sections: missing persons, unidentified persons and unclaimed persons. The latter involves remains that have been identified but haven’t been claimed by a relative or acquaintance.

“This is the first database of its kind that is available to public users, so if you have a missing loved one, you can enter a case into NamUs and we’ll verify it with law enforcement before it’s published — but you can initiate,” Mr. Matthews said.

The database also contains information from law enforcement agencies that recovered unidentified remains from the scene, along with details from medical examiners and coroners such as estimated age and ethnicity, the circumstances in which the remains were found, medical history and any identifying physical attributes.

“It’s the legal duty of the medical examiner to make positive identifications,” explained Dr. Michael Caplan, Suffolk County’s chief medical examiner. Most identifications are based on fingerprints or dental records, he said, but identity can also be determined by examining distinctive markings, such as tattoos or scars from documented surgical procedures.

But even with these techniques, Dr. Caplan and Mr. Matthews said there are several reasons a case can ultimately go cold. For instance, medical examiners can pull dental records once a person is reported missing. But if no such report is filed, that may not be possible.

“In our society, again, unfortunately, we have a lot of people that live alone or are estranged or not in regular contact with a social network,” Dr. Caplan said. “That’s one of our big things — we run into snags either if we don’t have a presumed ID or if we have a presumed ID, but the means to confirm that are stonewalled.”

Analyzing DNA is never an expert’s first option, as that process can be labor intensive and take weeks — longer if the sample has degraded, he said.

“The fact is, we can’t put a puzzle together with a single missing piece,” Mr. Matthews said. “We need the missing person’s report and we need to get their biometrics. If I don’t have dental, DNA or fingerprints, I have no means of comparing any exclusions — none.”

Sometimes a missing person’s fingerprints are already on file, but their presumed remains have decomposed to the point that DNA is no longer recoverable. In other cases, dental records may be available but the remains may not include a head.

“Then it’s DNA or nothing,” Mr. Matthews said.

Awareness of the NamUs database and input from loved ones can help fill in blanks and facilitate the process of elimination, Mr. Matthews said. Coverage of high-profile cases such as the Long Island serial killer have helped raise awareness about the organization and led to new inquiries and DNA samples in other cases. For instance, a torso discovered in Manorville in 2000 was later determined to belong to the same woman whose head, hands and right foot were discovered in 2011 at Gilgo Beach.

“Every time there’s a major story run with a newspaper, I’ll get somebody that’s never heard of it that brings us a piece of information — one more piece that I didn’t know about, that our whole team didn’t know about,” Mr. Matthews said.

Mr. Matthews has seen cases in which families go years without being able to confirm a missing loved one’s remains but find a match once a DNA sample is submitted to NamUs.

“We have some pretty powerful tools, but that’s why it’s a matter of getting the database to be as full as it can be — and then you have the best chance for making a match somewhere,” Dr. Caplan said.

Since September, New York State medical examiners and coroners have been required to share fingerprints and other identifying information with NamUs. Dr. Caplan was involved in providing background information to state lawmakers.

Not all states have the same requirements, but Mr. Matthews said he wished they did, since remains found in New York could be linked to a missing person in another state.

What, then, happens to remains that are never unidentified?

When the Suffolk County medical examiner’s office establishes that all attempts to make an identification have failed, it contacts the county’s public administrator, whose primary role is to curate the estates of the deceased. That person then works with local funeral directors to arrange a burial — not just for unidentified remains, but for people whose remains were never claimed. Unlike New York City, Dr. Caplan explained, the county doesn’t have a potter’s field.

“I think it’s important to really do everything we can to identify these bodies and to not have to bury them unidentified, but I also feel that at some point, if we can say with good conscience that we have exhausted those attempts, that we ultimately do give them a place of burial,” he said.

Once the remains are buried, the county retains a case file noting which police agency was involved. Information also remains indefinitely with NamUs and the public administrator retains records of where remains have been interred.

“Are things hard? Yes. Will we ever just throw something away and forget about it? No,” Mr. Matthews said. “We’ll always try to go back for as long as we can. It belongs to somebody.”

Top photo caption: The Manorville location where a man in 2012 found a human skull. (Credit: Paul Squire, file)