Sole 9/11 survivor: Kevin Shea tells his story

During his three-year probationary period as a freshman New York City firefighter in the late 1990s, “probie” Kevin Shea was tasked with keeping a journal of his daily experiences on rotation. After each tour or call, he would scribble notes into multiple composition notebooks, type them up and even add colored images.

As a third-generation firefighter, entering this profession was sort of his birthright. However, the job did not pique his interest at first. In his youth, Mr. Shea said, he always dreamed of being a filmmaker. His family encouraged him to give firefighting a shot, since they knew him as the “type of guy to rush in” and help people.

“I didn’t think I was going to love it. It’s for anyone else, but not me, but I loved it,” Mr. Shea said. “I fell right into the role. I became this ideal probationary firefighter that was always there, off duty and on duty.”

The fire chiefs took notice of his commitment and awarded Mr. Shea the rare opportunity to choose any firehouse he wanted to be stationed at permanently. Because of his interest in working with hazardous materials, the eager probie chose FDNY Engine 40/Ladder 35, located in Manhattan’s Lincoln Square.

He could not have predicted that on Sept. 11, 2001, the 34-year-old would be found alone at ground zero — the sole survivor of his 13-member firehouse.

Shea answers the alarm

Early on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, Mr. Shea was off-duty and had just completed a 16-hour shift. He was relieved around 7:30 a.m. and was having a cup of coffee with the other firefighters when, at 8:46 a.m., they were alerted a plane had crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

At the time, Ladder 35 had not yet been called to the scene, but when a second plane hit the South Tower and the alarm sounded, Mr. Shea immediately jumped on the rig.

“I asked [my captain], ‘Sir, is this terrorism?’ and he only said three words: ‘It appears so,’” Mr. Shea said. “There were four guys in the back … they said not a word, like a pin could drop. You don’t hear anything except the sound of the engine starting up and getting ready to go.”

He shared one memory of watching a firefighter write his Social Security number in marker on the calf of his pants — in case his body needed to be identified. In that moment, Mr. Shea said, he knew he had to be ready for whatever he would have to face once he stepped off the rig and into the chaos.

Alone in the rubble

Arriving at the World Trade Center, Lt. John Ginley informed Mr. Shea there were not enough breathing masks to go around, so he directed him to remain outside one of the towers. While the rest of Ladder 35 was inside the South Tower, Mr. Shea was positioned in the staging area with other area first responders.

Seeing extra masks and oxygen tanks unclaimed, he grabbed the equipment he needed from the staging area, geared up and went toward the South Tower to try to locate the other members of his company.

All he saw inside was pitch black darkness, which made pinpointing any familiar helmet badge numbers very difficult. Wanting to continue to help, he teamed up with other firefighter “orphans” to start putting out cars in flames near the South Tower.

What happened next transpired in just 9.5 seconds: Everything began to vibrate; a gigantic dark cloud of debris formed overhead and someone screamed for the firefighters to run. As the South Tower rapidly came crashing down, Mr. Shea was thrown into the air, landed on the ground and, in a semiconscious state, crawled away from the falling structure.

As the debris cleared and recovery commenced, Mr. Shea was found about 200 feet from where the tower fell. When he was pulled from the rubble, still semiconscious, he had a broken neck, was missing most of his thumb and had suffered other grave internal injuries. Later, he also developed retrograde amnesia because of the trauma.

“[One of the guys] said, ‘I don’t know how to tell you this, but you may have lost your thumb,’” Mr. Shea said. “My immediate response was to say, ‘That’s okay, I have another thumb,’ and I lifted up my other hand — he laughed at that, and he said, ‘You know what, he’s probably okay.'”

Strapped to a spine board, Mr. Shea was taken to an underground garage for safety. As the North Tower fell, his rescuers threw a tarp over his body to protect him. When he was eventually transported to a hospital in New Jersey, doctors told him if his head was tilted 45 degrees more in transit, he would have become a quadriplegic.

The aftermath

In the first 24 hours after the twin towers fell, Mr. Shea’s family believed he was dead, including his brother Brian. The retired firefighter got emotional talking about his brother’s desperate search for him.

“He rushed to my firehouse, then he rushed to the debris to try to find me … and that’s when he heard about the unaccounted-for list,” Mr. Shea said. “Then he heard there were some guys in the hospital, and he was the one that first located [me] in the hospital.”

When Mr. Shea woke up in the hospital, he had no recollection of the buildings coming down. With the help of others piecing the events together, memories gradually flooded back and the painful reality of losing his entire firehouse sank in. The next hurdle he had to face was: What’s next?

Only a week or so after being released from the hospital, Mr. Shea returned to the firehouse in a neck brace in full uniform. In between the hundreds of funerals and memorials, he continued his duties serving others during this tremendously difficult time. From doing chores around the firehouse to raising money for families who lost loved ones, Mr. Shea tried to help where he could, while in his condition.

“It was just so overwhelming for me — there’s something called survivor’s guilt — why am I alive and everyone else dead?” he said. “I was actually so happy to be alive and see the other firefighters in the house — they want to celebrate my life, but at the same time, we have to have a face of solemness.”

Shea moves forward with remembrance

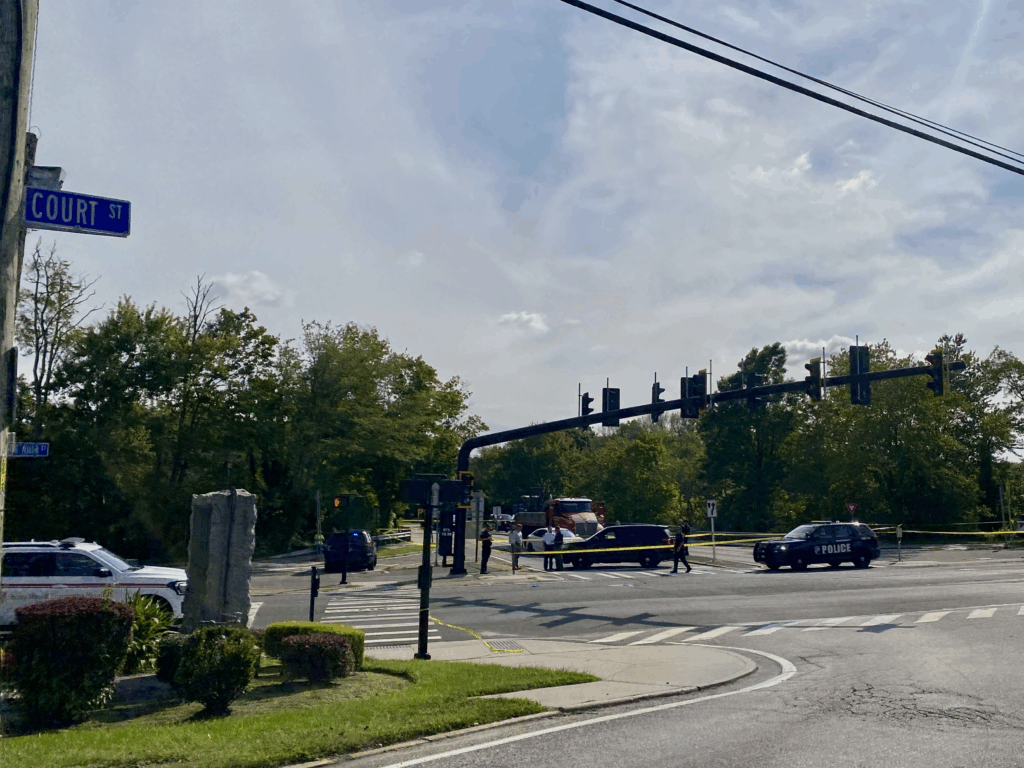

Healing from trauma was not a single turning point in Mr. Shea’s life, but an ongoing emotional journey. In the 24 years since the attacks, his FDNY community helped turn his dream geodesic dome-home in Baiting Hollow into a reality. He built a wildlife preserve in Nicaragua and kickstarted humanitarian efforts in that country. He continues to be an environmental steward, dedicate his time to serving others and volunteering, and he has even participated in community theater. Today, he is running for public office in Riverhead Town.

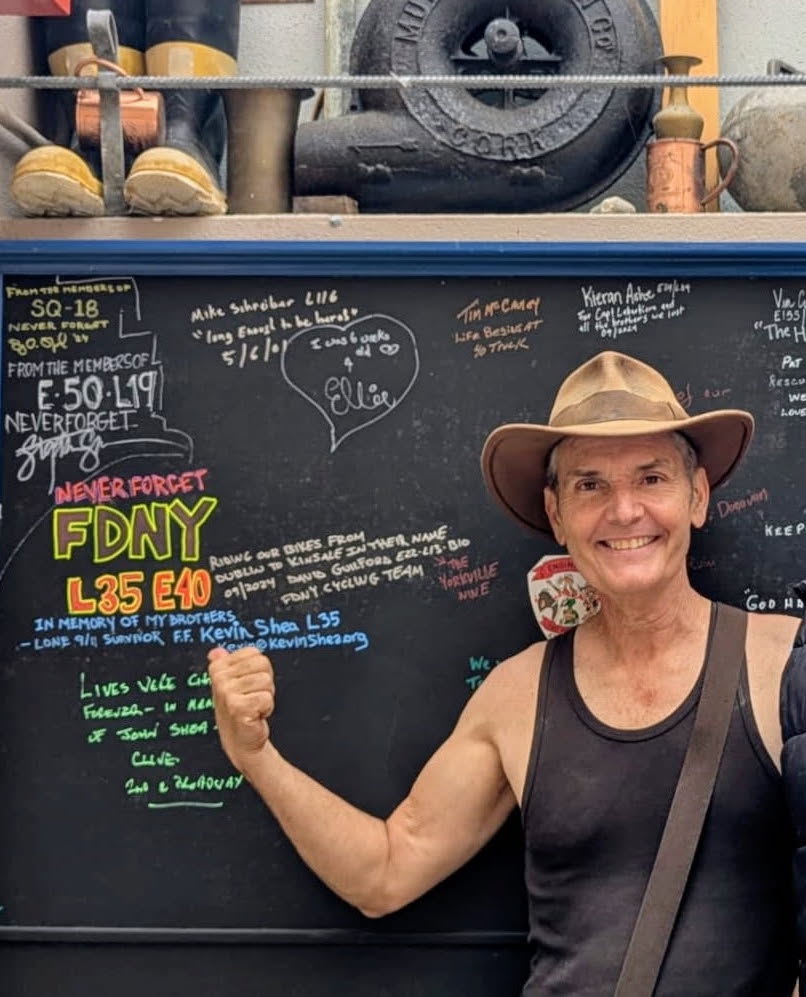

Mr. Shea and his partner recently journeyed to Ireland, the birthplace of his grandparents, and visited the Ringfinnan Garden of Remembrance in Kinsale. Planted there are 343 trees in honor of each first responder who lost their life on 9/11. During this visit, Mr. Shea spent time at each tree dedicated to his Ladder 35 brethren and paid a special tribute to his fallen captain, Frank Callahan.

Each year on Sept. 11, he goes back to FDNY Engine 40/Ladder 35 to salute those he lost, and pays his respects at other 9/11 memorials throughout the day. Mr. Shea said he hopes that sharing his story will impact others positively, fuel a greater sense of hope and preserve the memory of the selfless acts of his fellow firefighters

“They did a public service to people, though they knew they may not come back,” Mr. Shea said. “I learned to develop a sense of community with people outside the fire department, and then I also got a better sense of what being with a family is — firefighters were my first feeling of being in a real family.

“[9/11] made me stronger in the sense that I don’t let [stuff] bother me as much anymore. I don’t feel like I need to do things because people tell me … I do things that are right for other people.”