Keeping track of history: When trains ruled the North Fork

The fifth story in the Keeping Track of History series takes a peak into the once-prevalent North Fork train stations.

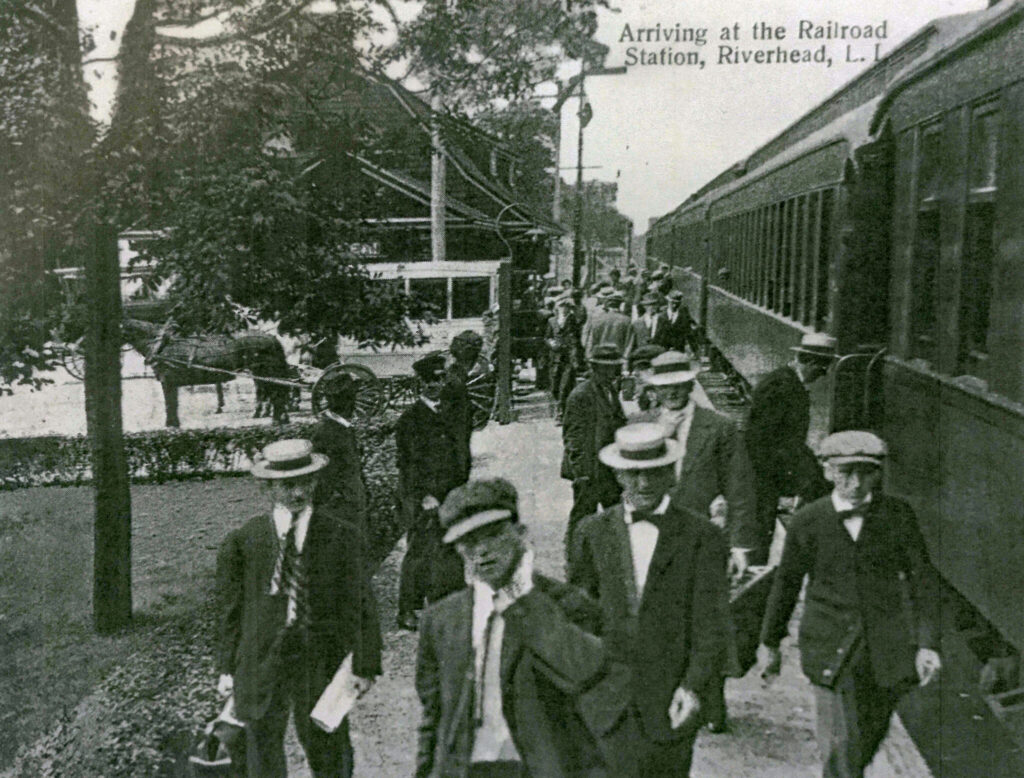

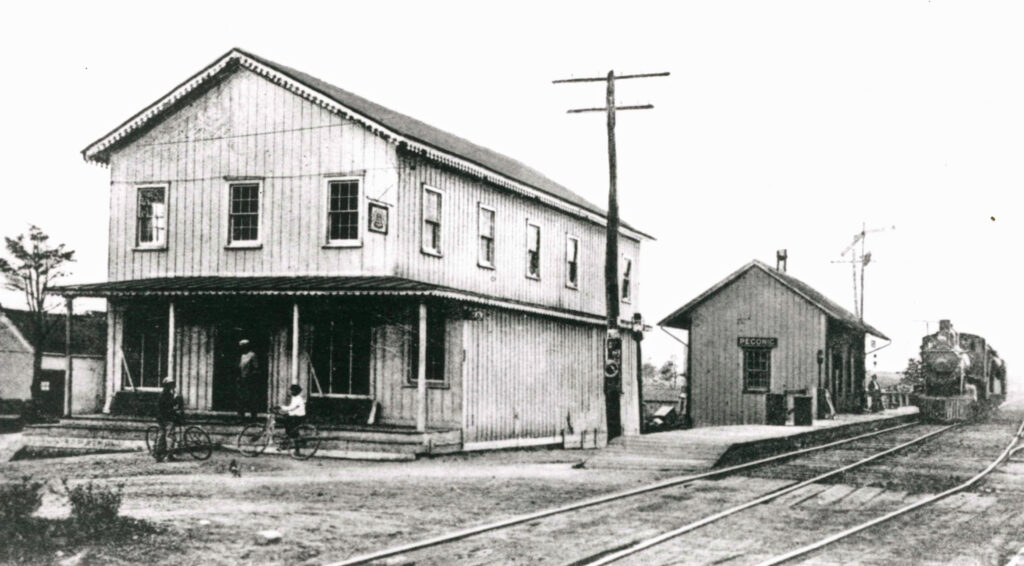

The North Fork once boasted a collection of LIRR train stations, spaced about three miles apart, for the convenience of passengers. This distance made it easy to travel between hamlets and move freight to and from the main hub in Riverhead. Taking the train was much faster than walking or taking a horse and buggy to the next village.

“If you walk normally, you can go about three miles in an hour. So if you have a station every three miles or so, the most somebody’s going to have to walk is a mile and a half to get to the station,” said George Walsh, trustee and archivist for the Railroad Museum of Long Island.

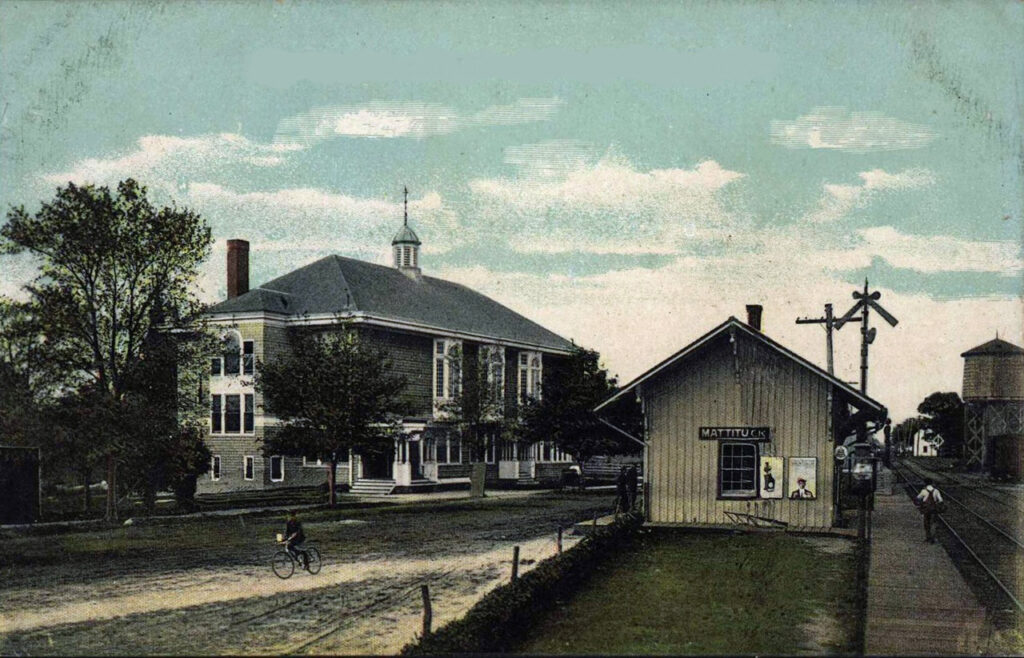

“People used to take the train to go from Greenport to Mattituck to visit friends and family,” said museum president Don Fisher.

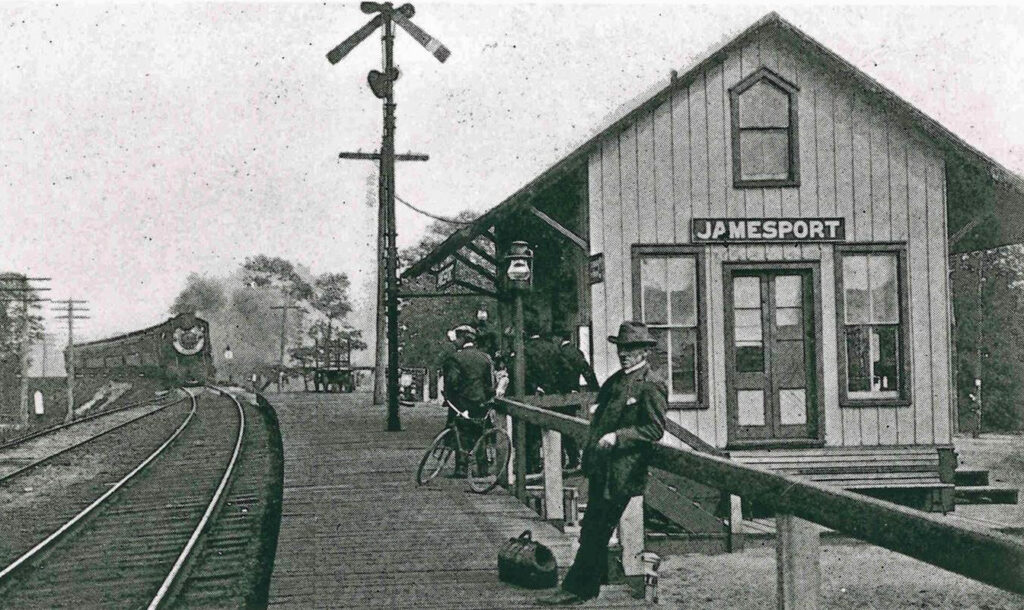

One of the destinations along the route to Greenport was the Methodist camp in Jamesport, located between South Jamesport and Washington avenues.

“People could literally step off the train with their bags, and you didn’t even have to come pick them up with a horse and wagon, they could walk there … and families would take a cottage for a week,” said Mr. Fisher. “The houses are still there, people live in them, and there’s a road, a circle, that comes in, and in the center, where they used to have like a common area with grass. Now the trees have grown up in there, but the road still goes in and circles around.”

Besides moving people along, the railroad also served to transport all manner of things to and from the North Fork. One of the most prominent products was ducks. At first, the birds were taken live from the farms in stock cars and dispatched when they reached the city.

“That was not an optimal way to deal with the ducks. Too many ducks died. You would lose your product on the two-hour, three-hour trip. It’s very stressful for the animals. So, that didn’t last for very long,” said Mr. Fisher.

Instead of shipping live, the farmers began processing the birds locally and placing them in barrels of brine. Once flash freezing became widespread, the birds were frozen and sent in refrigerated cars.

“The feathers we used for down, for bedding, pillows, clothing, and the ducks were used, consumed altogether,” said Mr. Fisher. “Now everything’s [shipped] on a truck.”

Possibly even more important to Long Island’s duck farming was the feed, which came via freight cars. Crates of feed came from suppliers like Purina to merchants, who then sold it to the farmers. Crescent Duck Farm had its own miniature industrial railroad to move the feed around the farm. This tiny train is now at the Railroad Museum facility in Riverhead.

Another important way the train served local farms was by transporting fertilizer components. These components were transported to fertilizer plants, which were built near the train yards. They had a crane house where each component was mixed as it traveled down a conveyor to the waiting farmer. “They could put it in bags, or they could run a truck right underneath this thing, and the various components would come down the chute into the back of the truck,” said Mr. Fisher.

Another key function of the railroad was to haul mail to postmasters to then distribute to residents. According to the classic Long Island Rail Road photo book, “Steel Rails to the Sunrise” by Ron Ziel, there was a rule stating that within a certain distance, measured door to door, the post office was responsible for carrying the mail from the train. Otherwise, the station master had to move the mail.

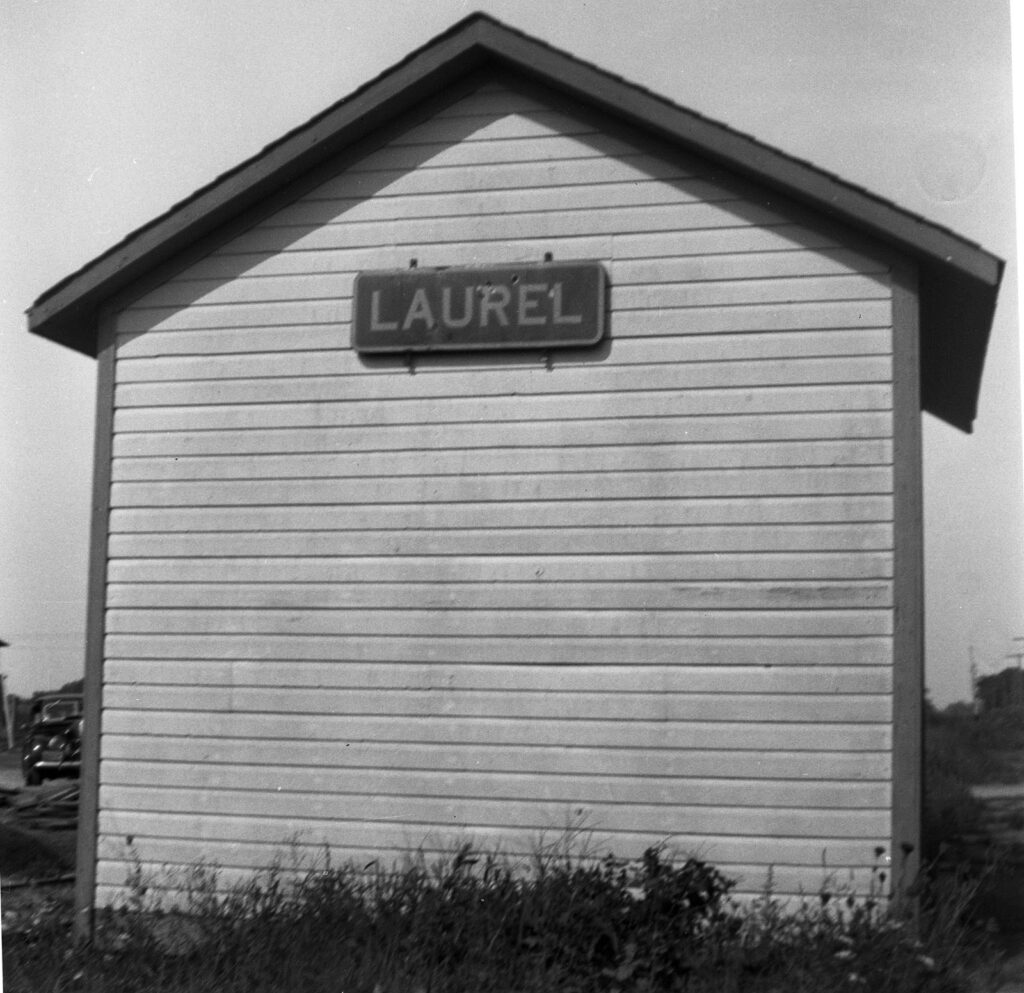

“When they built [the station in Laurel], the door was on the south side of the station, facing the tracks. And the post office manager said, ‘You guys are responsible for bringing the mail to us.’ And the Long Island Railroad station master called up what they called buildings and bridges, the B&B department, and said, ‘Come out here, we need a door on the north side of the building.’ So the railroad sent the carpenters out,” said Mr. Fisher. “And now the station agent called up the postmaster at Laurel post office, and said, ‘Get your tape out and come down and measure to the door again.’ So out comes the postmaster with his wheel, he measured the footage, and they were inside the line.”

After the Pennsylvania Railroad bought the Long Island Rail Road, many of the large, beautiful station buildings were removed or downsized to shelters. Some stations, like Aquebogue, Jamesport, Peconic and Laurel, were shuttered. After the LIRR was taken over by the MTA, the cuts deepened.

“Once we got past World War II, and we got into the ’50s, people were making money and the economy was good. Everybody wanted a car,” Mr. Fisher said.

“And the automobile industry, the bus industry, were instrumental in getting rid of trolleys and also tearing down railroads. We built the Eisenhower Interstate Highway System … They didn’t need the train anymore,” he continued.

This downsizing continued, until service was actually discontinued for a time in the 1960s, and the LIRR ran buses for two decades, from 1962 to 1982.

“When you got a bus here, you went to Huntington, because the bus went up Sound Avenue after it left Riverhead, it stayed on 25A into Huntington. You got off the bus in Huntington, and you got on a train in Huntington that took you the rest of the way to Jamaica and to Penn Station,” said Mr. Fisher.

Service resumed, and though there are more riders on the weekends than at other times, passengers are still rolling into North Fork train stations.

“We’ve had that problem, that challenge, of getting people to ride,” said Mr. Fisher. “We’ve got more trains running today than I can remember since I was a little boy. We actually have four round-trips to Greenport, and we have an additional, fifth round-trip here to Riverhead.”