East End’s homeless population faces daunting challenges

The affordable housing crisis has affected all of Long Island, but it has hit the East End’s homeless population especially hard, according to interviews with area advocacy groups, charities and outreach services.

“Typically, there was a fair amount of [rental] housing, but since the pandemic that has all gone away,” said Dan O’Shea, executive director of the Riverhead-based Maureen’s Haven, a homeless outreach program serving the East End. “I can’t find a migrant or a senior citizen an affordable place to live on the East End. It’s impossible.”

Advocates for homeless people described the scenario on the East End as a perfect storm — an unprecedented confluence of economic, demographic and technological forces that together have decimated affordable housing across Long Island, but particularly on the East End.

For decades, there were plenty of available East End rentals during the off-season, keeping prices in a reasonable range. But the COVID-19 pandemic drove a significant demographic shift, as more and more people moved out east permanently.

That sent real estate prices soaring, and houses that used to be rented out in the off-season have nearly all been sold. What little of the long-term rental market that remains in the region, experts said, has been gobbled up by AirBnB, VRBO and other short-term rental services.

“When the pandemic hit, so many people moved out here that a house that may have been a rental for 10 years suddenly comes on the market, and the houses that were $400,000 are now worth $800,000, so they’re all being sold off,” Mr. O’Shea said.

Cathy Demeroto, executive director of the Southold-based Center for Advocacy, Support and Transformation, agreed.

Ms. Demeroto said CAST — which supports underserved and vulnerable populations in Southold Town and Shelter Island with food, shelter, education, employment and health care — has seen a significant increase in the number of homeless clients on the North Fork.

She said CAST is currently working with 29 households comprising 63 individuals who have been displaced and need support, versus “five or six households” prior to the pandemic.

“In addition to having people who are homeless, we have people doubling or tripling up in housing units that are not adequate or safe, and that’s a major issue as well,” she said.

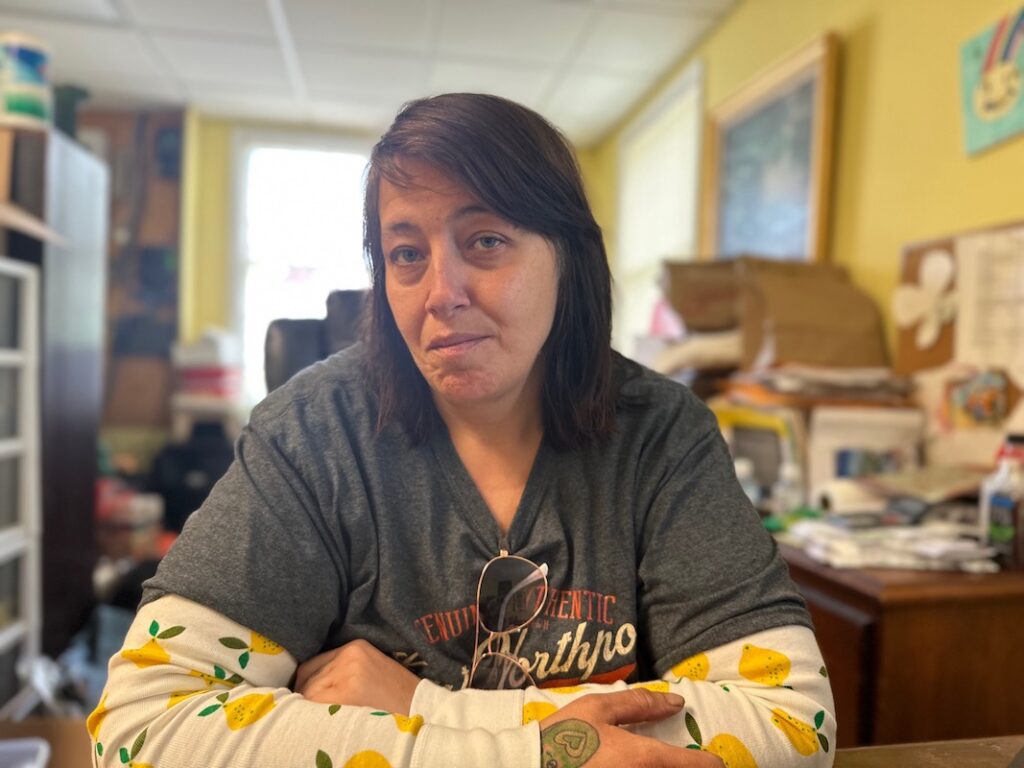

Experts say that a variety of personal crises can lead to homelessness, from addiction, mental health issues and domestic abuse to the many Long Islanders who slowly slid below the poverty line over the course of the pandemic —like Sherry Nucci.

Ms. Nucci, 43, recently made her seasonal transition from sleeping in North Fork shelters to living in a tent in woods behind a strip mall in Coram. A single mother, she had to turn over care of her son to her sister to keep him out of the same shelters where she stays.

Raised in Ronkonkoma, Ms. Nucci graduated from Sachem High School in 1999, the daughter of a single mom and a father who was incarcerated for decades. Ms. Nucci said her troubles began accumulating several years ago, around the time her son was 10 years old.

She said her rent for a studio apartment in Sayville suddenly began climbing in $50 increments every few months, from $900 to $1,200. She was working two jobs — one at 7-Eleven and another at a Dollar Tree store — and could no longer afford the rent.

“I couldn’t do that no more,” she said, “which eventually led me to the [county] Department of Social Services, but, sadly enough, the housing I found through them was in a bad area — a lot of criminal activity and drugs and all kinds of things,” she said. “And I had a kid that was 10.”

During this period, Ms. Nucci was running a dizzying daily gauntlet just to get her and her son through each day. “I had two jobs, so after school he had to go to day care,” she said. “So, I would leave my first job, take a bus to the school and pick him up, then take him to the day care, and then go to my second job,” she said. “My mom would get him out from the day care, and she’d meet me at the apartment and when I got home from work, they’d both be there.”

Soon Ms. Nucci was forced to move into a county shelter, which she said was no place for a child. In desperation, she turned to a sister with whom she had never gotten along, and asked her sister to take them in.

“She said, ‘I can take him, but I can’t take you in,’ ” Ms. Nucci recalled. “It was heartbreaking. It’s not an issue of me not being able to support him. I don’t drink or do drugs … so it wasn’t like I was incapable of caring for him. It was just that I wanted to keep him out of the shelter.”

Now, three years later, her son has settled into a new life at his aunt’s home, where he has his own room and belongings.

“He said, ‘Mom, I want to be with you, but I don’t want to be in a shelter.’ And I don’t blame him.”

Ms. Nucci’s son is not alone. A first-of-its-kind nationwide study of the 2018-19 school year by the Center for Public Integrity found that hundreds of North Fork students were homeless.

Using district level federal education data, the analysis estimated rates of homelessness among students in local schools. In Riverhead, data reported 324 homeless students — or 5.7% of the district’s total enrollment of 5,718. In Greenport, 5.3% of the district’s students, or 35 out of 667 , were homeless; in Southold, 2.1% of 778 students, or 16, were homeless and in the Mattituck-Cutchogue district, 1.4% of 1,126 students, or 16, were homeless.

Ms. Nucci said she turns over her monthly food stamps to her sister to help pay for her son’s upbringing and spends her days volunteering at Maureen’s Haven.

“I like it here,” she said last week. “They really care about you.”

Maureen’s Haven runs an emergency shelter program during winter months on the East End, partnering with houses of worship on both the North and South forks to house homeless Long Islanders from Nov. 1 to April 1 each year.

Last winter, Ms. Nucci said, she spent the night in nearly every shelter on the North Fork.

“I’ve been to Greenport, I’ve been to Mattituck, Aquebogue, Southold, you know, different places every night during the winter season,” she said, adding that in the more than three years since she lost the studio in Sayville,“I still have not made it back from that, to have my own housing.”

Since April 1, Ms. Nucci has been living in a tent with a friend behind a strip of commercial buildings in Coram. “It’s been quite an adventure,” she said. “I camped before, but I never did it for survival reasons.”

Ms. Nucci said that county shelters are too dangerous to sleep in unless absolutely necessary. At a shelter in Smithtown, Ms. Nucci said, she had her belongings stolen “over and over and over again.”

“The last time it happened a lady threatened to burn my hair on fire.”

So, like many Long Islanders down on their luck or between jobs, Ms. Nucci began living outdoors during the warmer months.

Ms. Nucci said those living outdoors tend to gravitate to railroad stations and woods behind big box stores like Target and Walmart.

“You blend in [at a train station], you don’t look like a homeless person, you don’t get attacked,” she explained.

She said that personally, she prefers pitching her tent behind Walmart superstores.

“They stay open late and they’re open early, and this is survival mode, so it’s safer to be near a place like that. If you need to freshen up, or use the bathroom, Walmart opens at 6 a.m. and closes, most of them at least, at 10 p.m. And they have everything you could ever need in there.”

Ms. Nucci said she’s been actively looking for work throughout the time she has been homeless. “I have 22 years of retail experience,” she said with pride. Despite 29 recent applications, mostly for retail positions, Ms. Nucci said, “no one’s hiring me.”

She has also worked as a home health care aide and in maintenance, “so I don’t mind getting dirty,” she said.

“Even if I don’t look good on paper, I’ve got a lot of experience.”

Ms. Nucci said she refuses to panhandle.

“I don’t believe in doing that,” she said. “If something is meant to come my way, it comes my way. I pray every day, sometimes multiple times a day, but I don’t panhandle.”

Ms. Nucci said that many of Long Island’s homeless population “are hidden.”

“They are deep, deep in camps, where it’s a lot harder to find these people. As we speak there could be 30 to 50 people out in the woods, way out so you would never find them,” she said. “It happens in more places than you’d think, even in the nicest towns.”

Despite the bleak outlook on Long Island, a 2022 federal report suggests that significant progress is being made nationally to combat homelessness.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2022 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report to Congress found that family homelessness is down more than 36% since 2010, veteran homelessness is down more than 55% since 2010 and unaccompanied youth homelessness has dropped 21% since 2017.